Writing Smart, 3rd edition - Princeton Review 2018

Editing

The editing process

So you’ve written well-constructed sentences and strung them together to make coherent paragraphs, with transitions in between. At this point you have a rough draft in front of you. We hate to say it, but when you have a rough draft, you’re still only about halfway there. Editing is the main work in writing excellent prose. It can be a tedious process eliminating words, sentences, even whole paragraphs, as well as moving text around and elaborating on certain points. But the results are well worth it.

When editing, try to read your work with an objective eye. You don’t need to remind yourself how hard you worked on a particular paragraph or sentence; you need to decide what should be done with a particular paragraph or sentence as it relates to the whole of what you are writing. You are trying to refine the whole piece. All concerns other than the quality of that piece need to be ignored. You must stomp out that unhelpful part of your ego (“This metaphor is fantastic; even if it doesn’t exactly work in this context, I need to keep it!”), and smother lazy urges (“Eh, it’s good enough as is”). Make sure you allow yourself as much time as possible for this process. It is not the most pleasant for the majority of writers, and you may need to fortify yourself with frequent breaks for fuel in the form of snacks and non-literary entertainment. But when you’re finished and have a polished final product in front of you, you’ll be glad you put in the time and effort.

If you’re editing a hard copy, your notations should be clear so that you know what you mean when you return to them later on. The notations on the next page are the proofreading marks that we will use in the editing exercises throughout this book. This does not mean you have to use these yourself; it means you can check back here when you are trying to figure out what a little squiggle might mean.

Editing usually takes place in at least three rounds. The first round should be focused on overall organization.

Round 1: organization

Organization of a paper allows that paper to be read and understood logically. Much of editing lies not only in particular words or sentences but in whole paragraphs and sections of text. This is particularly true of longer pieces. On your first read-through of a longer piece, look for larger organizational issues.

Often your writing will seem particularly clear to you, when you are in fact missing important transitions or referring to a paragraph that doesn’t come for another three pages. To avoid these problems, you need to spend some time at the rough draft stage of your paper. This is when you have everything you are going to include in the paper already written, but you haven’t yet read through it for spelling or continuity, nor have you (most likely) added footnotes or other references. Before you go on to the fine-tuning stage, you need to make sure that your structure is sound.

First, read through the paper. Is it logical? Does everything seem to be in the proper order? Take notes as you read, indicating parts that seem unclear. Then divide your paper into sections. If your paper sets forth an opinion or argument, read through and separate it into the pieces of evidence that support your point. If your paper is a descriptive piece, separate it into the different facets of your subject.

One effective technique is to literally cut the paper with scissors. Compositions written in longhand should be photocopied, and works composed on the computer should be printed out as hard copies. Once you have separated your paper into pieces, spread them out and see if you can organize them into a more coherent whole. Experiment a bit here. Sometimes a paragraph that previously seemed dull or weak will take on a whole new life when it begins the body of a paper. Conversely, a paragraph that you had grown attached to can be exposed in this process as a nasty little parasite that is weakening the whole structure and coherence of your piece. Try many different setups, and keep a record of the ones that work best. It may be helpful here to make several copies and paste together your three best attempts at organization. You can also have other people read the paper at this stage, after having strung it together in a new way. Your friends or teachers can let you know whether you are being daring or just disorganized.

Round 1 Questions

· Is this the logical way I would argue this point if I were talking to someone?

If you wouldn’t talk this way on your best arguing day, there is probably a better way to organize your piece. Often ideas will come to you as you are writing, and you will include them as you think of them. This is all well and good, but it probably means that they are somewhat out of order. Once you have a rough draft, look at all the evidence and information you include. You can even put the subject of each paragraph on a note card, then move them around on the desk until they are well ordered. You may also want to read newspaper or magazine articles and essays to get examples of writing that flows logically and builds up to a main point, or thesis.

· Do the paragraphs transition smoothly from one to the next?

This has much to do with the last and first sentences of paragraphs. Readers know intuitively that when a new paragraph begins, they should expect a somewhat new thought; but they also expect it to relate in some way to the thoughts just expressed. If there is no immediate connection, either create an entirely new section—not just a new paragraph—or write a transition sentence to begin the new paragraph. This transition sentence performs essentially the same function as a segue a comedian might make, like “So, speaking of kangaroos, I was talking to an Australian guy the other day….” It allows the audience to follow your train of thought. You can still allow your reader to make some deductions, but don’t force him to guess how things fit.

· Are related paragraphs near each other?

If you refer to a dog named Gary in one paragraph, then refer to the dog again later as just “Gary,” you need to ascertain that the reader knows to whom or to what you are referring. Be aware of this especially if you move paragraphs around in the editing process.

· Does each paragraph explain itself well to the reader, or does it rely on additional, outside knowledge that should also be included?

In general, never assume knowledge on the part of the audience. This is true even if you’re writing for a teacher or professor. For example, let’s say in a history paper you write the following sentence: “After the war, there was a lot of trouble for everyone cleaning it up.” Which war? Every subject in your paper should be explicitly introduced, defined, or explained.

Round 2: Style

When you have a structure you are comfortable with, you are ready for the next stage: editing for style.

You will probably notice some awkward sentences as you go through the reorganizing round. At this point, you will return and look for them mercilessly. If you are using pen and paper to compose, put these changes onto the pasted-together rough draft from your first round of edits. If you are using a computer, you can simply enter any corrections onto a saved version. It is probably helpful to print out that new version and put your edits on the hard copy. You can then enter them once you have gone through this second round.

When writing, try to get as much down as possible, but when editing, make sure that each piece is serving its appropriate function in its appropriate place.

Introductory sentences should be both engaging and concise. At the beginning of a paragraph, a paper, or an essay, you must try to open the door (yes, that’s a metaphor) for your reader so she will look inside and want to enter. Whatever type of paper you are writing, you are creating a world that the reader will enter, even if only for a few sentences. Your opening sentence should orient your reader so she knows what you will be talking about and from what point of view.

Read each body paragraph carefully and determine whether your writing clearly communicates your logic. Scrutinize each sentence. Poke. Prod. If you find a sentence that doesn’t work, rewrite it. If it still doesn’t work after one or two rewrites, start a new sentence from scratch. Sometimes it is easier to create anew rather than work to fix something that is broken. You should also check for spelling, grammar, and punctuation here. Keep a dictionary and a copy of The Chicago Manual of Style on hand to check these fine points.

Round 2 Questions

· Does this sentence convey its idea clearly?

When you were writing you knew what you meant, but will the reader know? “I felt as I always do when I hear Rachmaninoff,” may mean you were frightened, exhilarated, or infuriated, but your reader will be unable to understand unless you open your private world of images to her. When you edit, think of this reader, and how each word, sentence, and paragraph would seem to her.

· Does each sentence flow from the previous one?

Paragraphs should form coherent wholes. If there is too large a jump from sentence to sentence, the reader will become confused and lose the train of thought you have established.

· Are any sentences unnecessary to the whole?

Extraneous sentences can bore a reader faster than anything else. In general, if within one paragraph you find two sentences that say the same thing, one of them can go. Of course, in certain circumstances repetition can be used for dramatic emphasis, and this is where you can again ask yourself, “Is this sentence necessary to the whole?” If not, strike it out.

· Are any words unnecessary to the whole?

Redundancy is lethal to good style; avoid unnecessary words.

· Is the point of view consistent?

Refer to the point of view section in the previous chapter. You should use only one point of view throughout a piece.

· Is the tense consistent?

For clarity’s sake, be consistent in your use of tenses.

· Does this sentence say exactly what I mean?

You had a particular point you wanted to get across within each sentence you wrote. Does the sentence say what you meant? Check to see if a certain word could be fine-tuned to be more exact. “I wanted to take a walk before it got too dark” is not the same thing as, “I was afraid it would soon be too dark for me to walk safely.” The first is matter-of-fact and slightly impatient, while the second implies a certain amount of trepidation, nervousness, and hesitation.

· Is this sentence true?

This relates more to honesty in writing. Before you allow a sentence like, “The lightning flashed and a tree shuddered next to me, but I was not afraid,” make sure that it is either literally true, or a very well-planned bit of misinformation, leading to humor or the like.

· Is there a variety of sentence structure in this paragraph?

While a certain amount of sentence structure repetition can lend your writing a particular rhythm, the same sentence structure over and over will cause your readers to feel frustrated. If you see five sentences in a row beginning the same way, with “if” or an —ing word, see if you can transform a few of them.

· Is each pronoun in this sentence necessary?

We are all subject to the modern-day plague of unnecessary pronouns. Chief among the culprits are “that,” “which,” and “it.” When you see any one of this unholy trio, try the sentence without it. Does it still work? If so, eliminate the pronoun.

· Does each pronoun refer to something the reader can understand?

You may find sentences that seem perfectly intelligible but have a mysterious floating pronoun. For example: It is very difficult to understand why there is violence in this world. The first “it” has no clear reference, and “this” preceding “world” makes it seem as though the writer has had some experience in other worlds, as does bringing up “the world” at all. The existence of violence is incomprehensible is a more concise way of expressing the same idea.

· Is the sentence grammatically correct?

Take no chances here. If you are unsure, look it up. While you can amend spelling mistakes, typos, and punctuation in the last round of editing (though you will have caught most mistakes by then), grammatical errors often demand a reconstruction of the sentence. This reconstruction is too messy to appear on the final version of a paper, so attend to it now.

· Do I avoid the passive voice?

That sounds much better than, “Has the passive voice been avoided by me?” doesn’t it? When possible, sentences should be in the active voice. If you have a long, unruly, or dragging sentence, passive voice may well be the problem.

· Does my verbal crutch appear anywhere?

A verbal crutch is a phrase or expression we use while speaking, sometimes to emphasize something or to (subconsciously) give ourselves more time to think. But often these crutches are used merely because they have become somehow embedded in our brains, and one result is that they turn up in our writing, too. Common verbal crutches include actually, basically, honestly, literally, weird, and for the record. If you know your verbal crutch, use the search-and-replace feature on your computer to search the document for its use. If you’re not aware of your crutch or are working on a hard copy, just be vigilant. Read your piece carefully and circle any phrases that are used multiple times to the point that they become distracting and meaningless.

· Do I have clichéd images?

Dark as night, bright like the sun, like a pack of vicious animals, on and on the cliché march goes. A cliché is an image that has been used so much and so often that it has actually been worn out. Readers are so used to seeing clichés that whatever power the image or saying once had is dismissed by the reader. Comb your writing for clichés. Whenever you see a phrase you recognize as overly familiar, strike it out.

· Have I gone crazy with adverbs, adjectives, and other description?

Adverbs, along with most forms of description, should be used sparingly. Description should suggest, not give every detail. Don’t overwhelm the reader.

· Do I sound like myself?

Yes, you should sound like yourself. Don’t try to seem more “writerly” or literary, as you will probably come off as trying too hard, or your meaning will get lost in a sea of complexity and words you found in the thesaurus. Your writing is a representation of you, so be true to who you are.

· Is there stylistic closure?

Closure ties together loose ends and allows readers to feel they have truly finished, instead of being cut off in some premature way. Most writing requires some sort of conclusion to provide closure. The length of your conclusion will usually depend on the length of your piece. Symmetry may serve as an effective stylistical tool in creating closure. If you begin your paper with an anecdote, ending with an anecdote can be beautifully symmetrical. This also works if you begin with a quotation, a theory, or a historical reference. Consistency of example allows you to give your readers a feeling of satisfaction when they have reached the end of your paper. No matter how you accomplish it, closure is why a conclusion is necessary to most writing.

Round 3: Proofread

Before you do this final read-through, you must incorporate your edits from Round 2. If you’re using a computer, you can enter these in the saved document. If you’re using a pen and paper, you should write another draft.

Proofreading is your opportunity to indulge that nitpicking tendency you have kept hidden from the world. Or, this may be your opportunity to develop that streak. In the third round, you are looking for any tiny errors that may be floating around in your almost perfect manuscript. You are checking things you have already checked, like spelling, punctuation, typos, indentations, numbering on pages, underlining or italicization of titles (italics are preferable if you have them), and capitalization of proper names. If you are writing on a computer, you have the benefit of the spell check, though a spell check cannot identify all errors. So be extra careful and proofread for spelling anyway. When it doubt, look it up. For points other than spelling, keep that copy of The Chicago Manual of Style or the MLA Handbook with you, and mercilessly check all fine points.

Editing Drill 1

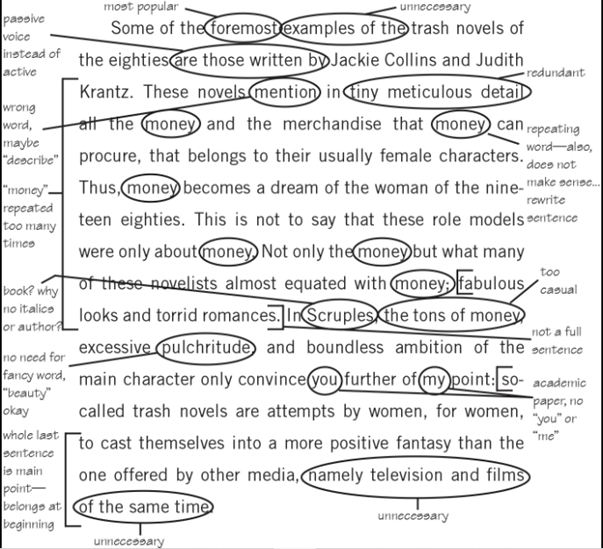

The following paragraph is part of a research paper discussing commercial novels of the 1980s, and it has many organizational and stylistic problems. Edit the paragraph, identifying these problems and addressing the questions brought up in the editing rounds we just discussed. Feel free to look back at previous chapters. Also keep in mind that since this paragraph is part of a research paper, it should have an academic tone. When you are done, compare the edits you made with our edits on the following page to see how they differ. If our edits don’t correspond exactly with yours, don’t be alarmed. Everyone edits in a different way, and your own personal style will have much to do with the words you choose to leave in or take out. After you have compared the two, look at the final version in which all the edits have been made. Are they what you would have done?

Some of the foremost examples of the trash novels of the eighties are those written by Jackie Collins and Judith Krantz. These novels mention in tiny meticulous detail all the money and the merchandise that money can procure, that belongs to their usually female characters. Thus, money becomes a dream of the woman of the nineteen eighties. This is not to say that these role models were only about money. Not only the money but what many of these novelists almost equated with money; fabulous looks and torrid romances. In Scruples, the tons of money, excessive pulchritude, and boundless ambition of the main character only convince you further of my point: so-called trash novels are attempts by women, for women, to cast themselves into a more positive fantasy than the one offered by other media, namely television and films of the same time.

Our version, with edits

Final version

The so-called trash novels of the eighties are attempts by women, for women, to cast themselves in more positive fantasy roles than those offered by other media. Jackie Collins and Judith Krantz wrote some of the most popular trash novels, which describe in meticulous detail the sumptuous financial situations of their heroines. Thus, these novels present financial stability as a dream of the woman of the 1980s. This is not to say that these role models were strictly mercenary. In these novels not only money, but what many of the novelists almost always equated with money—fabulous looks and torrid romances—represent the fantasies of women of the eighties. In Scruples, a novel by Judith Krantz, the money, beauty, and boundless ambition of the main character further demonstrate this point.

Editing Drill 2

The following is a personal essay in response to this question:

Please provide us with a one-page summary of personal and family background. Include information on where you grew up, parents’ occupations, any siblings, and perhaps a highlight or special memory of your youth.

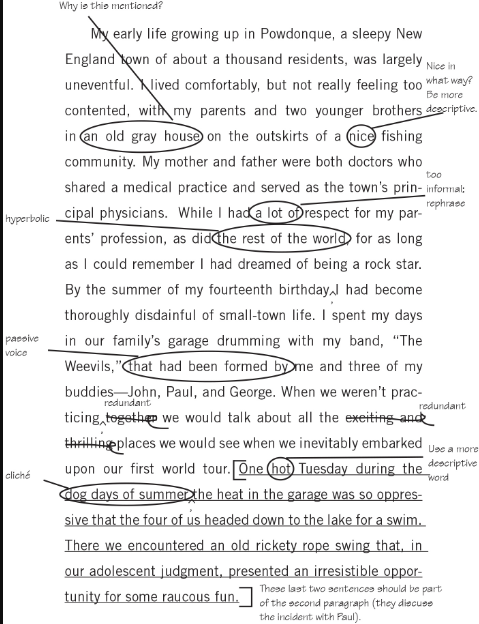

Edit the essay for organization and style. Keep in mind the that this is a personal essay, and thus aims for a conversational tone. Then, review the edited version and compare our edits with your own. While you should not worry if your edits do not match exactly, do try to determine the differences in the edits. When you are done comparing the two drafts, look to the final version to see how the edits were accommodated.

My early life growing up in Powdonque, a sleepy New England town of about a thousand residents, was largely uneventful. I lived comfortably, but not really feeling too contented, with my parents and two younger brothers in an old gray house on the outskirts of a nice fishing community. My mother and father were both doctors who shared a medical practice and served as the town’s principal physicians. While I had a lot of respect for my parents’ profession, as did the rest of the world, for as long as I could remember I had dreamed of being a rock star. By the summer of my fourteenth birthday I had become thoroughly disdainful of small-town life. I spent my days in our family’s garage drumming with my band, “The Weevils,” that had been formed by me and three of my buddies—John, Paul, and George. When we weren’t practicing together we would talk about all the exciting and thrilling places we would see when we inevitably embarked upon our first world tour. One hot Tuesday during the dog days of summer the heat in the garage was so oppressive that the four of us headed down to the lake for a swim. There we encountered an old rickety rope swing that, in our adolescent judgment, presented an irresistible opportunity for some raucous fun.

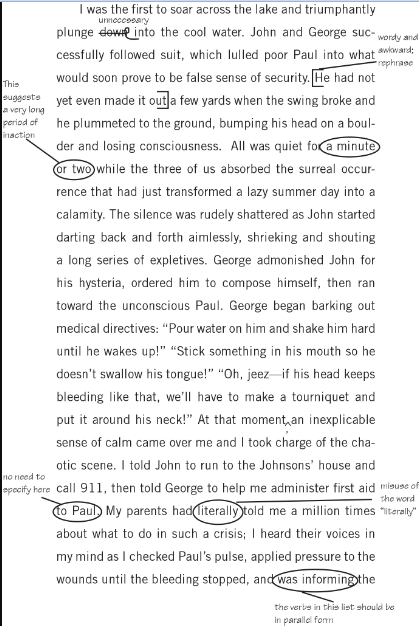

I was the first to soar across the lake and triumphantly plunge down into the cool water. John and George successfully followed suit, which lulled poor Paul into what would soon prove to be false sense of security. He had not yet even made it out a few yards when the swing broke and he plummeted to the ground, bumping his head on a boulder and losing consciousness. All was quiet for a minute or two while the three of us absorbed the surreal occurrence that had just transformed a lazy summer day into a calamity. The silence was rudely shattered as John started darting back and forth aimlessly, shrieking and shouting a long series of expletives. George admonished John for his hysteria, ordered him to compose himself, then ran toward the unconscious Paul. George began barking out medical directives: “Pour water on him and shake him hard until he wakes up!” “Stick something in his mouth so he doesn’t swallow his tongue!” “Oh, jeez—if his head keeps bleeding like that, we’ll have to make a tourniquet and put it around his neck!” At that moment an inexplicable sense of calm came over me and I took charge of the chaotic scene. I told John to run to the Johnsons’ house and call 911, then told George to help me administer first aid to Paul. My parents had literally told me a million times about what to do in such a crisis; I heard their voices in my mind as I checked Paul’s pulse, applied pressure to the wounds until the bleeding stopped, and was informing the paramedics of what little I knew of Paul’s medical history. Paul made a full recovery, and the incident at the lake was soon reduced to an amusing anecdote among friends.

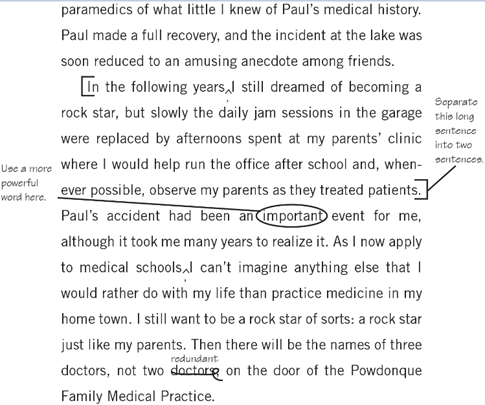

In the following years I still dreamed of becoming a rock star, but slowly the daily jam sessions in the garage were replaced by afternoons spent at my parents’ clinic where I would help run the office after school and, whenever possible, observe my parents as they treated patients. Paul’s accident had been an important event for me, although it took me many years to realize it. As I now apply to medical schools I can’t imagine anything else that I would rather do with my life than practice medicine in my home town. I still want to be a rock star of sorts: a rock star just like my parents. Then there will be the names of three doctors, not two doctors, on the door of the Powdonque Family Medical Practice.

Our version, with edits

Final version

My early life growing up in Powdonque, a sleepy New England town of about a thousand residents, was largely uneventful. I lived comfortably, if discontentedly, with my parents and two younger brothers on the outskirts of a quaint fishing community. My mother and father were doctors who shared a medical practice and served as the town’s principal physicians. While I had a healthy respect for my parents’ profession, as did the rest of the community, for as long as I could remember I had dreamed of being a rock star. By the summer of my fourteenth birthday I had become thoroughly disdainful of small-town life. I spent my days in our family’s garage drumming with my band, The Weevils,” that I had formed with three of my buddies—John, Paul, and George. When we weren’t practicing we would talk about all the exciting places we would see when we inevitably embarked upon our first world tour.

One sweltering August Tuesday the heat in the garage was so oppressive that the four of us headed down to the lake for a swim. There we encountered an old rickety rope swing that, in our adolescent judgment, presented an irresistible opportunity for some raucous fun. I was the first to soar across the lake and triumphantly plunge into the cool water. John and George successfully followed suit, which lulled poor Paul into what would soon prove to be false sense of security. He had barely made it out a few yards when the swing broke and he plummeted to the ground, striking his head on a boulder and losing consciousness. All was quiet for a moment while the three of us absorbed the surreal occurrence that had just transformed a lazy summer day into a calamity. The silence was rudely shattered as John started darting back and forth aimlessly, shrieking and shouting a long series of expletives. George admonished John for his hysteria, ordered him to compose himself, then ran toward the unconscious Paul. George began barking out medical directives: “Pour water on him and shake him hard until he wakes up!” “Stick something in his mouth so he doesn’t swallow his tongue!” “Oh, jeez—if his head keeps bleeding like that, we’ll have to make a tourniquet and put it around his neck!” At that moment an inexplicable sense of calm came over me and I took charge of the chaotic scene. I told John to run to the Johnsons’ house and call 911, then told George to help me administer first aid. My parents had so often instructed me about what to do in such a crisis; I heard their voices in my mind as I checked Paul’s pulse, applied pressure to the wounds until the bleeding stopped, and informed the paramedics of what little I knew of Paul’s medical history. Paul made a full recovery, and the incident at the lake was soon reduced to an amusing anecdote among friends.

In the following years I still dreamed of becoming a rock star, but slowly the daily jam sessions in the garage were replaced by afternoons spent at my parents’ clinic. I would help run the office after school and, whenever possible, observe my parents as they treated patients. Paul’s accident had been a watershed moment for me, although it took me many years to realize it. As I now apply to medical schools I can’t imagine anything else that I would rather do with my life than practice medicine in my hometown. I still want to be a rock star of sorts: a rock star just like my parents. Then there will be the names of three doctors, not two, on the door of the Powdonque Family Medical Practice.

Finally…

There are some people who benefit from more than three drafts of a paper. You must become accustomed to your own ways of writing to determine if you are one of these people. Every writer is unique, and eventually you will develop your own personal style of editing.

Recommended reading

The Chicago Manual of Style, The University of Chicago Press.

William Strunk and E. B. White, The Elements of Style, Macmillan.

Miss Thistlebottom’s Hobgoblins, The Careful Writer’s Guide to the Taboos, Bugbears, and Outmoded Rules of English Usage, Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.