Practical argument: A text and anthology - Laurie G. Kirszner, Stephen R. Mandell 2019

Casebook: Should every american go to college?

Debates, casebooks, and classic arguments

Since Harvard College was founded in 1636, American higher education has reflected the history of the United States—economically, socially, and culturally. In the early days of the country, a college education was a privilege for the elite few. The nineteenth century—a period of economic expansion—saw the development of the state university system, which educated many engineers, teachers, agricultural experts, and other professionals who participated in the country’s industrial boom. After World War I, the City College of New York provided a free, quality college education to many working-class students, including immigrants, at a time when they were effectively barred from other colleges. However, the most significant expansion in American higher education occurred after World War II, when the GI Bill gave returning veterans money for tuition and living expenses so they could attend college. Enrollment skyrocketed, and many people credit the GI Bill for helping to create postwar prosperity and a large middle class.

In the decades since the first GI Bill was passed, the number of colleges and universities in the United States has increased steadily: as of 2017, there were over 4,360 degree-granting institutions in the United States. Nearly 40 percent of Americans now have at least a two-year college degree, and roughly two thirds of high school graduates enroll in college after graduation. Statistics show that college graduates earn an average of about $17,500 more annually than those who have only a high school diploma. This financial reality, along with the need for a highly educated and competitive workforce in an increasingly global marketplace, has led some to argue that the federal government should do more than it already does to make sure that more—and perhaps even all—Americans attend college. Such proposals raise fundamental questions about higher education. How should colleges maintain academic standards even as they admit more students? How should such institutions control costs? Is higher education a right in the same way that a high school education is? Should everyone go to college? Wouldn’t high-quality vocational training make more sense for many?

The following four essays address these and other questions, exploring the importance of a college degree and suggesting new ways of viewing postsecondary education. In “College’s Value Goes Deeper than the Degree,” Eric Hoover argues that a college education offers many tangible and intangible benefits. In “Stop Saying ’College Isn’t for Everyone,’ ” Andre Perry argues that every student should be prepared to go to college, even if they ultimately do not attend. In “The College Trap,” J. D. Vance argues that contrary to popular belief, subsidizing colleges is not an effective way to promote opportunity. Finally, in “What’s Wrong with Vocational School?” Charles Murray argues that too many people are going to college and that some should consider vocational school as a viable alternative.

COLLEGE’S VALUE GOES DEEPER THAN THE DEGREE

ERIC HOOVER

The Chronicle of Higher Education published this essay on April 22, 2015.

Scholastic skepticism is contagious. Pundits and parents alike continue to second-guess the value of a college degree. After all, the recession has changed the way many Americans look at big-ticket purchases; plenty of families worry that today’s expenses will not pay off tomorrow.

Not surprisingly, today’s cost-conscious public views college price tags with a wary eye. According to the Pew Research Center survey of the American public, only 35 percent said colleges were doing a “good” job in terms of providing value to students and parents; 42 percent said “only fair,” and 15 percent said “poor.”

A curious thing happened when college graduates were asked about the value of their own degrees, however. In the Pew survey, 84 percent of those with degrees said college had been a good investment; only 7 percent said it had not.

Why? Perhaps it’s because assessing the value of a college education is not a hard-and-fast calculation. Sure, diplomas help Americans land better jobs and earn higher salaries, and one can estimate the financial return on those investments. Yet the perceived benefits of attending college go well beyond dollars.

In the Pew survey, all respondents were asked about the “main purpose” of college. Forty-seven percent said “to teach knowledge and skills that can be used in the workplace,” 39 percent said “to help an individual grow personally and intellectually,” and 12 percent said “both equally.”

These findings echo the words graduates often use to describe the benefits of their college experiences. Typically, those benefits are intangible, immeasurable, and untethered to narrow questions about what a particular degree “got” them.

Evan Bloom’s diploma will tell you only so much about him. As an under-graduate at the University of California at Berkeley, Mr. Bloom considered several majors. He wanted to take hands-on courses that would require creative thinking. Finally, he settled on architecture.

After graduating, in 2007, Mr. Bloom worked in construction management for a few years, but life inside a cubicle bored him. Recently, he decided to pursue a passion for which he has no credentials: cooking.

Mr. Bloom, 25, is the co-founder of Wise Sons Jewish Delicatessen, a catering business in San Francisco. The venture, which serves the public out of rented space once a week, has yet to become a full-time, brick-and-mortar business. That’s likely to change as soon as investors come aboard.

Mr. Bloom believes his out-of-classroom experiences prepared him to become a restaurateur. At Berkeley he was active in the student government, honing his networking skills. As a member of the university’s Hillel chapter, he and a friend, Leo Beckerman, cooked weekly meals for groups of 250. The experience inspired them to start Wise Sons together.

More than once, Mr. Bloom has thought about the power of connections made in college. An alumnus of his fraternity helped him get an internship with the contractor for whom he later worked. And had he not met Mr. Beckerman at a bar one night years ago, he might still be doing something he enjoys less than making pastrami and rye bread.

“My classes were great, but it was really everything else I was doing that mattered the most,” Mr. Bloom said. “It was tapping into this whole sphere of influences.”

“Basic, Fundamental Training”

The way her life unfolded, Vanessa Mera didn’t end up needing her bachelor’s degrees in psychology and economics. After graduating from the University of Miami in 2001, she and her sister took over their parents’ import-export-distribution business, called VZ Solutions Inc., in Miami.

Still, Ms. Mera, 31, says her time in college was crucial. As a freshman, she had expected to major in biology and go on to medical school. Over time, she realized that she didn’t want to become a doctor. “In college, you come in thinking one thing about yourself,” she said, “and you leave thinking in a completely different way.”

Ms. Mera, who had attended a private all-girls high school, believes that interacting with people of different backgrounds helped her overcome her shyness. So, too, did the time she spent studying in Spain.

Surrounded by many high-achieving students at Miami, Ms. Mera developed a competitive streak. If you want to land a good internship, she learned, you must put yourself out there.

“I realized that just because you had good grades didn’t mean you were going to get anywhere,” Ms. Mera said. “Without those four years, I wouldn’t be the businessperson I am today. I wouldn’t have the confidence.”

Jane Knecht can relate. She enrolled at the University of Virginia in the late 1970s, unsure of what she wanted to study. She signed up for an introductory rhetoric course. “I didn’t even know what the word meant,” she said.

Soon, Ms. Knecht couldn’t get enough. In a course on rhetoric and social theory, she recalled, a professor gave students three unrelated pieces of writing and told them to synthesize an argument that tied them all together. At first, she froze up, worried that she couldn’t do it. Then the writing flowed.

As Ms. Knecht practiced public speaking and wrote a mountain of papers, her self-confidence soared: “It was basic, fundamental training.”

Ms. Knecht graduated in 1982 with a degree in speech communications. She had planned to go to law school, but instead spent seven years at home with her two children before entering the work force. At 52, she’s now director of business development at the Water Environment Research Foundation, in Alexandria, Virginia.

Without a bachelor’s degree, Ms. Knecht figures, she wouldn’t have been considered for the job. Many of her colleagues have master’s degrees or Ph.D.’s. Moreover, she believes college prepared her for day-to-day challenges.

“Everything in my job is relationship-based,” said Ms. Knecht, who on a recent afternoon was preparing to run a conference call with business associates in Australia, followed by a board meeting. “My classes helped me recognize the importance of listening and effective negotiating, and how to go into new situations, which I do all the time.”

Billy Ray, 59, described his degree as a door that led him to prosperity. His parents were poor, as were most of his childhood friends. “We were on the bottom rung,” he said. “I didn’t like where I was, and I wanted to change that.”

When Mr. Ray enrolled at Stephen F. Austin State University in 1970, he found himself surrounded by people with fatter wallets and high aspirations. This inspired him. “I was associating with a different level of people,” he said. He put himself through college by working for a construction company during the summers.

Mr. Ray says the contacts he made in college were just as crucial as the courses he took. After graduating with a degree in business administration, Mr. Ray went to work for the construction company as a licensed plumber. Later, a good friend from Stephen F. Austin offered him a job selling trucks at a dealership. “I went from making good money to really good money,” he said.

Mr. Ray, who lives in Lufkin, Texas, is now a regional manager for De Lage Landen, a financial-services company. He and his wife, Alys, own a 3,000-square-foot house, and they recently purchased a second home, in Austin, where both of their sons graduated from the University of Texas.

Having written all those tuition checks, Mr. Ray understands why some people question the value of college. “You’re losing four years of work time and thousands of dollars,” he said. “Do you ever get it back?”

“And the value of going to college, he believes, is only increasing.”

Still, Mr. Ray, the only one of three brothers to finish college, said he would have a much lower-paying job without a bachelor’s degree (his current position requires one). And the value of going to college, he believes, is only increasing. “If they don’t get that degree,” he said, “they’re going nowhere.”

![]()

READING ARGUMENTS

1. In your own words, paraphrase Hoover’s thesis.

2. Where does Hoover state his thesis? Why does he wait so long to do so? What information does he present before he states it? Why?

3. What is the relationship between paragraphs 6 and 7? What transition is Hoover making at this point in the essay?

4. Hoover supports his thesis with several anecdotal examples. What point do these examples make? What are the strengths and weaknesses of this kind of evidence? What other types of evidence could Hoover have included?

5. In what respects is this essay an evaluation argument?

STOP SAYING “COLLEGE ISN’T FOR EVERYONE”

ANDRE PERRY

This essay was published on The Hechinger Report, an education website, on September 1, 2015.

Let’s admit that the “college isn’t for everyone” cliché is really a euphemism for those people aren’t smart enough for college.

At historically black fraternity Kappa Alpha Psi’s Grand Chapter Meeting, or Conclave, in New Orleans last month, the phrase again reared its ugly head, when audience members repeatedly embedded it in questions to a panel in black male achievement hosted by the White House Initiative on Educational Excellence for African American Students.

The “college isn’t for everyone” statement isn’t false; it’s just disingenuous. According to the Lumina Foundation, a funder of The Hechinger Report, nearly 39 percent of Americans between 25 and 64 years old hold at least a two-year college degree. However, only 28 percent of blacks, 23 percent of Native Americans, and 20 percent of Latinos possess at least a two-year degree. Meanwhile, 44 percent of whites and 59 percent of Asians hold degrees.

Clearly, not everyone goes to college. But the “not for everyone” verbiage is most frequently used in conversations about improving education for low-income students. Soon thereafter comes the unimaginative bailout for underachieving kids—vocational training.

Let’s be clear. We should prepare all students as if they are going to college.

There is a perception that trades require a completely different foundation than a college prep curriculum. The national push for career and technical education (vocational) focuses on “skills he or she can provide to a business” as opposed to those designed to prepare students for college.

This doesn’t mean that all students shouldn’t be prepared with rigorous courses. One study found that “students in career pathways outperformed their peers on the number of credits they earned in STEM and AP classes while also earning higher GPAs in their CTE classes.” The study goes on to recommend rigorous curricula that don’t hinder students’ chances of going to college.

Intimating that we remove academic rigor because certain kids can’t handle it actually downgrades professions as well as the academic sophistication needed to be successful for any career choice in the 21st century. There are high-paying jobs that only require a high school diploma. For instance, a college degree won’t predict one’s career performance as a coder.

Famous college dropouts like Steve Jobs, Mark Zuckerberg, and Bill Gates are often used as examples of how high-paying jobs are available for those with only high school or community college training. But Zuckerberg and Jobs aren’t examples of why colleges don’t work; they are examples of why colleges must change. These men shopped for courses they needed, gained networks, and acculturated (to a degree).

“But Zuckerberg and Jobs aren’t examples of why colleges don’t work; they are examples of why colleges must change.”

College and universities must change. Now acting as high-priced finishing schools where the middle-class networks, colleges need to become more affordable, flexible, relevant, and inclusive. In particular, they must create programs that are relevant and affordable to the populations they are supposed to serve.

What if the first two years of college were treated like the 13th and 14th grades? Obama’s free community college plan addresses the reality that postsecondary education is requisite for personal and social vitality. The college debt argument within ’college isn’t for everyone’ debates is vital, but it’s a red herring. If you think college is expensive, try living without a degree.

One may assume brothers of a black Greek letter organization, whose membership is predicated on the matriculation, initiation, and graduation of undergraduates, think that college is for everyone. Black Greek letter organizations, which represent one of higher education’s most cherished traditions, must trumpet the college is for everyone horn.

I was happy to learn about Kappa Alpha Psi’s Diamond in the Rough campaign at the “Klave.” Diamonds in the rough exposes “young men across the nation to an intense college preparatory and scholarship access program.” The program provides resources for ACT/SAT test preparation and scholarships for each graduating class of “Kappa Leaguers” and increases access to scholarship opportunities for them nationally. Individual preparation is critical.

College isn’t just for people whom we deem ready. We actually need to educate and transform people whom we’re not ready for. Achievement as a result of selectivity isn’t education—it’s selectivity.

It’s not a bourgie fantasy to expect plumbers and electricians to know the building blocks of language arts, math, and science. It’s also not fantasy that fraternal organizations see people who are interested in the trades as future member/collegians. By growing membership and graduation rates, fraternities and sororities offer a bridge from low-income communities to college graduation stages.

College may not be for everyone, but it should be.

![]()

READING ARGUMENTS

1. What is Perry’s thesis? Where does he state it?

2. In paragraph 9, Perry refers to the examples of college dropouts like Mark Zuckerberg and Bill Gates. What point does he use them to make?

3. Perry writes, “It’s not a bourgie fantasy to expect plumbers and electricians to know the building blocks of language arts, math, and science” (para. 15). What does bourgie mean? To what does the phrase bourgie fantasy refer?

4. What does Perry mean in paragraph 14 when he says, “We actually need to educate and transform people whom we’re not ready for”?

5. In his opening sentence, Perry asserts, “Let’s admit that the ’college isn’t for everyone’ cliché is really a euphemism for those people aren’t smart enough for college.” Why is “college isn’t for everyone” a cliché? Do you agree with his assessment? Why or why not?

THE COLLEGE TRAP

J. D. VANCE

This essay appeared in the National Review in its January 9, 2014, issue.

A few years ago, a friend learned that a mutual acquaintance had accepted a job with an elite D.C. law firm, at a starting salary of $160,000. She turned pre-law almost overnight. Because I was thinking about law school myself, I knew that those high-paying jobs were vanishing for all but the luckiest graduates. My friend was undeterred: She took an extra year of classes to raise her GPA for the applications (incurring thousands in debt in the process) and crammed for the law-school admissions test. It was an admirable effort. But eventually the reality of the employment market set in, and she took a different job. She never did go to law school.

My friend displayed a classic middle- and working-class mindset. In his 2010 book How Rich People Think, Steve Siebold criticized the almost religious belief “that master’s degrees and doctorates are the way to wealth.” I had that belief too—it’s why I wanted to go to law school in the first place—and so does virtually everyone I’ve ever known. When you grow up at the bottom or even in the middle, advanced education is the Holy Grail. Parents mortgage their homes and children donate their plasma (seriously) to pay for it.

Lately, writers have questioned whether many people spend too much on college and get too little in return. This fear has motivated recent proposals to encourage online education or make a $10,000 bachelor’s degree available to everyone. But there is a deeper problem with the college cult than the diminishing value of certain degrees: In our zeal to give many a college education, we’ve made it an employment barrier for those who lack it.

You can imagine the reaction if, tomorrow, Congress passed a worker-identification law with the following provision: “Only those who carry their federal ID card may apply for jobs that pay more than $45,000; ID cards may be obtained from government vendors for $100,000.” The country would erupt in protest. Yet this is what college does. When two people apply for a job, and they’re alike in every way except schooling, the employer will almost always hire the more educated. That’s true even of the many jobs that don’t require a college degree. As economists Neeta Fogg and Paul Harrington recently found, a shocking 39 percent of new graduates are working such jobs.

Academics call this phenomenon “degree inflation.” In an economy populated by college graduates, bachelor’s degrees become necessary just to get your foot in the door. A host of professions—photographers, lab technicians, and equipment operators—have seen their ranks swell with college graduates, despite the absence of any obvious need for forklift drivers to have studied Michel Foucault. The New York Times recently reported that these new education requirements often have little to do with ensuring that employees possess a particular skill set. Instead, they’re an easy way to winnow the applicant pool: There are so many degree holders these days that you can eliminate all non—degree holders and still have plenty of people to hire from.

Unfortunately for many working-class Americans, that winnowing process falls hardest on them. As it’s currently played, the college-education game simply isn’t fair.

Part of the problem is that bright low-income children don’t apply to colleges that match their talents. The brutal irony is that, for the poor, the colleges with the highest sticker prices are free (or close to it) because of generous need-based aid. So there’s much to be said for policies that make low-income students aware of the options they have.

Still, there are many subtle ways that colleges discriminate against working-class students. Take, for example, the admissions process. A common critique of modern affirmative action is that class is a far better metric of misfortune than race, and that colleges should adjust their admissions preferences accordingly. The underlying assumption is that a poor student gets no admissions boost relative to a “wealthy student. But this actually understates the problem: Poor students are actively disadvantaged in the process. In a recent study, Princeton sociologists Thomas Espenshade and Alexandria Radford discovered that at private colleges—whose graduates have, on average, significantly better employment prospects than graduates of public schools—a poor white student is three times less likely to receive an admissions offer than his wealthy counterpart with the exact same grades and SAT scores. Race doesn’t explain this, and neither do grades or standardized tests.

What does explain it? One factor is that a lot of colleges are not “need-blind”: They are simply less likely to accept students who will need more financial aid. Another answer is obvious to anyone who’s applied to a prestigious college. To gain admission to these places, you don’t just need scores and grades, you need a padded résumé—internships, sports, extracurriculars, and leadership positions. The Princeton Review, a test-coaching company, estimates that up to a third of the average college application is based on exactly these “soft factors.” But for a working-class child, chess club, baseball, and student government usually give way to an after-school job. And admissions officers apparently care little about an applicant’s experience bagging groceries.

When these students do get into college, they often encounter other barriers unique to their circumstances. Most parents complete their kid’s financial-aid forms, for instance, but a lot of poor students must fight through the bureaucratic morass alone. That’s harder than it sounds: For the 7.5 million impoverished kids living with single moms, filling out Dad’s income figures on the annual financial-aid application requires serious detective work. One recent graduate I spoke with had to borrow money from a friend so that he could pay his first month’s rent and security deposit. Even though he’d been awarded tens of thousands in financial aid, the money wasn’t disbursed until a month after classes had started.

This is the minefield that progressives and many conservatives have labored to make the only path to the top in modern America. Of course, we married ourselves to college for all the right reasons: Policymakers wanted to help people, and statistics showed us that college graduates earned millions more than everyone else over a lifetime. The next step was obvious: Send more people to school. It was one of the truly bipartisan issues in our society. In the 2000 presidential campaign, Al Gore offered a $10,000 tuition deduction while George W. Bush promised more funding for scholarships and Pell Grants.

But to the extent that politicians viewed college education as a panacea for rising inequality and reduced upward mobility, they were wrong. The average college graduate may make more money, but anyone can tell you that a Harvard degree pays more than one from the online University of Phoenix—so statistics about the “average” graduate tell us little. The truth is that graduates of America’s worst colleges have little to show for their time besides mountains of debt. And the graduates of those colleges are disproportionately poor.

Liberals justify the tens of billions we spend on college education on at least one other ground: that it ensures that our society is better prepared for the “new economy.” President Obama has repeatedly committed the United States to leading the world in college-graduation rates by 2020, a goal that, if achieved, would allegedly cure many social ills. But if college is the key to the future, then it makes little sense that South Korea, Japan, and Canada—the best-educated societies on the planet—rank far behind the United States in per-person productivity. Meanwhile, Singapore and Switzerland, among the few countries that outrank us in terms of per capita GDP, lag behind the U.S. in college completion.

So, at the national level, the link between college education and productivity is virtually nonexistent. If we’re not creating much value with the billions we spend on education, it’s worth asking what those billions have bought. And the answer is: good jobs for university employees, and a social system that disadvantages the poor.

Economists have long understood that subsidies work best when producers are able to increase output. It’s a very intuitive concept. If universities can’t produce more employable graduates but are still taking in loads of cash, they’ll spend it somewhere else. In practice, this meant that dorms grew plusher, professors earned more, administrative staffs swelled, and an industry of for-profit colleges sprouted from nowhere. A Goldwater Institute report found that since 1993, administrative outlays have increased by 61 percent per student. My own alma mater, Ohio State, employs six non-teachers for every full-time faculty member. This is where our education dollars go.

“So, at the national level, the link between college education and productivity is virtually nonexistent.”

Addressing this lack of practical skills, while helpful, is still only a partial solution. A big part of the problem is that by the time many of our poor kids reach college age, they’re so far behind the curve that they’ll never catch up. University of Chicago economist James Heckman, a winner of the Nobel Prize, has shown that far too many poor children lack the soft skills—such as the abilities to delay gratification and to cooperate—that help set the successful apart from everyone else. His research has found that high-quality early-childhood education is the most productive investment in the lower class. In fact, it’s an investment that pays returns: We spend so much less in incarceration costs, welfare payments, and the like that we actually save tax dollars. The case for investing more in early-childhood education is based not just in fairness but in economics.

Not all early-childhood education is created equal. As progressives push for an expansion of the largely ineffective, federalized Head Start program, there is a better option: subsidizing early education in the same way we subsidize college education. Give people money and let them decide how to spend it.

Conservatives have supported vouchers for all the right reasons: Vouchers give kids the opportunity to escape a failing school, they give parents a choice, and they force educators to compete. Yet it needs to be said that vouchers grow less effective as children age. Skills beget skills, and knowledge begets knowledge: Heckman’s research shows that a good preschool produces significantly better results for children than does a good high school. The most effective voucher programs will target our youngest kids, not those nearing adulthood.

This means that subsidizing college is a terrible way to promote opportunity. Of course, college still has value. There are millions of jobs that require advanced education. And many of our universities produce cutting-edge technologies that create real growth and improve our nation’s future. But we have reached a point of diminishing returns. Our society turns its nose up at 19-year-old plumbers while reinforcing the notion that every undergraduate is “going places.” All the while, our government finances the creation of more undergraduates while doing little to help young kids close the skill gap.

The irony is that our economy needs more plumbers and fewer undergraduates. And America’s poor need more opportunity, not heavily subsidized pieces of paper.

![]()

READING ARGUMENTS

1. Vance begins his essay with an anecdote about a friend. What point does he make with this story? Is this an effective introduction? Explain.

2. In paragraph 3, Vance says that “there is a deeper problem with the college cult than the diminishing value of certain degrees.” What does the “college cult” refer to? What is the “deeper problem”?

3. Where in his essay does Vance use an argument by analogy? Do you find it persuasive?

4. According to Vance, admission to a prestigious college or university is dependent on “soft factors” (para. 9). What are they? How does this situation disadvantage less affluent applicants?

5. Vance concedes that the “average college graduate may make more money” (12), but argues that this statistic tells us very little. Why?

6. In his conclusion, Vance says, “Our society turns its nose up at 19-year-old plumbers while reinforcing the notion that every undergraduate is ’going places’ ” (19). Do you think his generalization is true? Why or why not?

WHAT’S WRONG WITH VOCATIONAL SCHOOL?

CHARLES MURRAY

The Wall Street Journal published this opinion piece on January 17, 2007.

The topic yesterday was education and children in the lower half of the intelligence distribution. Today I turn to the upper half, people with IQs of 100 or higher. Today’s simple truth is that far too many of them are going to four-year colleges.

Begin with those barely into the top half, those with average intelligence. To have an IQ of 100 means that a tough high-school course pushes you about as far as your academic talents will take you. If you are average in math ability, you may struggle with algebra and probably fail a calculus course. If you are average in verbal skills, you often misinterpret complex text and make errors in logic.

These are not devastating shortcomings. You are smart enough to engage in any of hundreds of occupations. You can acquire more knowledge if it is presented in a format commensurate with your intellectual skills. But a genuine college education in the arts and sciences begins where your skills leave off.

In engineering and most of the natural sciences, the demarcation between high-school material and college-level material is brutally obvious. If you cannot handle the math, you cannot pass the courses. In the humanities and social sciences, the demarcation is fuzzier. It is possible for someone with an IQ of 100 to sit in the lectures of Economics 1, read the textbook, and write answers in an examination book. But students who cannot follow complex arguments accurately are not really learning economics. They are taking away a mishmash of half-understood information and outright misunderstandings that probably leave them under the illusion that they know something they do not. (A depressing research literature documents one’s inability to recognize one’s own incompetence.) Traditionally and properly understood, a four-year college education teaches advanced analytic skills and information at a level that exceeds the intellectual capacity of most people.

There is no magic point at which a genuine-college-level education becomes an option, but anything below an IQ of 110 is problematic. If you want to do well, you should have an IQ of 115 or higher. Put another way, it makes sense for only about 15 percent of the population, 25 percent if one stretches it, to get a college education. And yet more than 45 percent of recent high-school graduates enroll in four-year colleges. Adjust that percentage to account for high-school dropouts, and more than 40 percent of all persons in their late teens are trying to go to a four-year college—enough people to absorb everyone down through an IQ of 104.

No data that I have been able to find tell us what proportion of those students really want four years of college-level courses, but it is safe to say that few people who are intellectually unqualified yearn for the experience, any more than someone who is athletically unqualified for a college varsity wants to have his shortcomings exposed at practice every day. They are in college to improve their chances of making a good living. What they really need is vocational training. But nobody will say so, because “vocational training” is second class. “College” is first class.

Large numbers of those who are intellectually qualified for college also do not yearn for four years of college-level courses. They go to college because their parents are paying for it and college is what children of their social class are supposed to do after they finish high school. They may have the ability to understand the material in Economics 1 but they do not want to. They, too, need to learn to make a living—and would do better in vocational training.

Combine those who are unqualified with those who are qualified but not interested, and some large proportion of students on today’s college campuses—probably a majority of them—are looking for something that the four-year college was not designed to provide. Once there, they create a demand for practical courses, taught at an intellectual level that can be handled by someone with a mildly above-average IQ and/or mild motivation. The nation’s colleges try to accommodate these new demands. But most of the practical specialties do not really require four years of training, and the best way to teach those specialties is not through a residential institution with the staff and infrastructure of a college. It amounts to a system that tries to turn out televisions on an assembly line that also makes pottery. It can be done, but it’s ridiculously inefficient.

Government policy contributes to the problem by making college scholarships and loans too easy to get, but its role is ancillary. The demand for college is market-driven, because a college degree does, in fact, open up access to jobs that are closed to people without one. The fault lies in the false premium that our culture has put on a college degree.

“A bachelor’s degree in a field such as sociology, psychology, economics, history, or literature certifies nothing.”

For a few occupations, a college degree still certifies a qualification. For example, employers appropriately treat a bachelor’s degree in engineering as a requirement for hiring engineers. But a bachelor’s degree in a field such as sociology, psychology, economics, history, or literature certifies nothing. It is a screening device for employers. The college you got into says a lot about your ability, and that you stuck it out for four years says something about your perseverance. But the degree itself does not qualify the graduate for anything. There are better, faster, and more efficient ways for young people to acquire credentials to provide to employers.

The good news is that market-driven systems eventually adapt to reality, and signs of change are visible. One glimpse of the future is offered by the nation’s two-year colleges. They are more honest than the four-year institutions about what their students want and provide courses that meet their needs more explicitly. Their time frame gives them a big advantage—two years is about right for learning many technical specialties, while four years is unnecessarily long.

Advances in technology are making the brick-and-mortar facility increasingly irrelevant. Research resources on the internet will soon make the college library unnecessary. Lecture courses taught by first-rate professors are already available on CDs and DVDs for many subjects, and online methods to make courses interactive between professors and students are evolving. Advances in computer simulation are expanding the technical skills that can be taught without having to gather students together in a laboratory or shop. These and other developments are all still near the bottom of steep growth curves. The cost of effective training will fall for everyone who is willing to give up the trappings of a campus. As the cost of college continues to rise, the choice to give up those trappings will become easier.

A reality about the job market must eventually begin to affect the valuation of a college education: The spread of wealth at the top of American society has created an explosive increase in the demand for craftsmen. Finding a good lawyer or physician is easy. Finding a good carpenter, painter, electrician, plumber, glazier, mason—the list goes on and on—is difficult, and it is a seller’s market. Journeymen craftsmen routinely make incomes in the top half of the income distribution while master craftsmen can make six figures. They have work even in a soft economy. Their jobs cannot be outsourced to India. And the craftsman’s job provides wonderful intrinsic rewards that come from mastery of a challenging skill that produces tangible results. How many white-collar jobs provide nearly as much satisfaction?

Even if forgoing college becomes economically attractive, the social cachet of a college degree remains. That will erode only when large numbers of high-status, high-income people do not have a college degree and don’t care. The information technology industry is in the process of creating that class, with Bill Gates and Steve Jobs as exemplars. It will expand for the most natural of reasons: A college education need be no more important for many high-tech occupations than it is for NBA basketball players or cabinetmakers. Walk into Microsoft or Google with evidence that you are a brilliant hacker, and the job interviewer is not going to fret if you lack a college transcript. The ability to present an employer with evidence that you are good at something, without benefit of a college degree, will continue to increase, and so will the number of skills to which that evidence can be attached. Every time that happens, the false premium attached to the college degree will diminish.

Most students find college life to be lots of fun (apart from the boring classroom stuff), and that alone will keep the four-year institution overstocked for a long time. But, rightly understood, college is appropriate for a small minority of young adults—perhaps even a minority of the people who have IQs high enough that they could do college-level work if they wished. People who go to college are not better or worse people than anyone else; they are merely different in certain interests and abilities. That is the way college should be seen. There is reason to hope that eventually it will be.

![]()

READING ARGUMENTS

1. Construct a syllogism for the deductive argument Murray uses in his opening paragraphs. Do you find this argument persuasive? Why or why not?

2. Murray makes a distinction between engineering and the natural sciences (on the one hand) and the humanities and social sciences (on the other). What difference does he identify? Why is this difference important to his argument?

3. Murray claims that too many people are going to four-year colleges. What cause-and-effect arguments does he use to support this claim? How do these arguments support his position on the issue?

4. More than once in his essay, Murray notes that the “intellectually unqualified” probably do not want to attend a four-year college, and he implies that if given the chance, they would choose not to. Do you think this is true? Do you believe Murray’s emphasis on personal choice strengthens his argument? Explain.

5. According to Murray, more people should go to vocational schools. What advantages does he see for those who choose careers in trades and crafts?

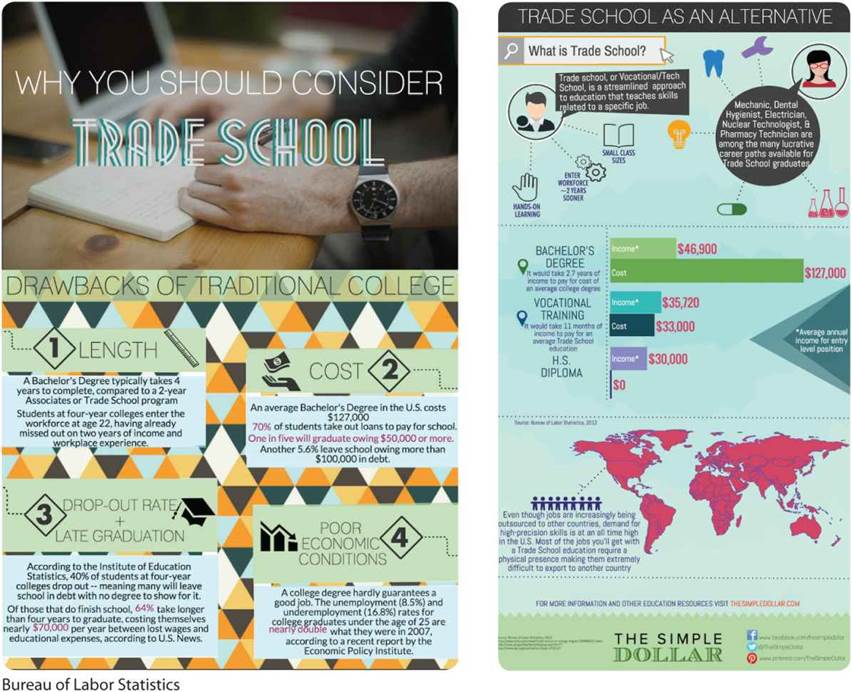

VISUAL ARGUMENT: WHY YOU SHOULD CONSIDER TRADE SCHOOL

The poster is divided into four sections with images and text. The first section is titled Drawbacks of traditional college. This section is again divided into four points and it reads, 1. Length (An image of a scale is shown): A Bachelor’s Degree typically takes 4 years to complete, compared to a 2-year Associates or Trade School Program. Students at four-year colleges enter the workforce at age 22, having already missed out on two years of income and working experience. 2. Cost (An image of a dollar is shown): An average Bachelor’s Degree in the U S costs 127,000 dollars.70 percent of students take out loans to pay for school. One in five will graduate owing 50,000 dollars or more. Another 5.6 percent leave school owing more than 100,000 dollars in debt. 3. Drop-out rate plus late graduation (An image of a graduation hat is shown): According to the Institute of Education Statistics, 40 percent of students at four-year colleges drop out - - meaning many will leave school in debt with no degree to show for it. Of those that do finish school, 64 percent take longer than four years to graduate, costing themselves nearly 70,000 dollars per year between lost wages and educational expenses, according to U S News. 4. Poor economic conditions (An image of a graph is shown): A college degree hardly guarantees a good job. The unemployment (8.5 percent) and underemployment (16.8 percent) rates for college graduates under the age of 25 are nearly double what they were in 2007, according to a recent report by the Economic Policy Institute.

The second section is titled Trade School as an alternative. An illustration below answers the question What is trade school? An illustration of a man on the left points to three points. The first point reads, Hands-on learning. An image of a palm is shown. The second point reads, Enter Workforce approximately 2 years sooner. An image of a workforce is shown. The third point reads, Small class sizes. An image of a book is shown. The man says, Trade School, or Vocational slash Tech School, is a streamlined approach to education that teaches skills related to a specific job. An illustration of a woman says, Mechanic, Dental Hygienist, Electrician, Nuclear Technologist, and Pharmacy Technician are among the many lucrative career paths available for Trade School graduates. The dialog box points to five illustrations: a spanner, a tooth, a bulb, a capsule, and three beakers.

The third section shows a bar graph. The text on the vertical axis of the graph reads, Bachelor’s degree. It would take 2.7 years of income to pay for cost of an average college degree. Vocational training. It would take 11 months of income to pay for an average Trade School education. H. S. Diploma. The bars representing the Bachelor’s degree read, Income asterisk: 46,900 dollars; Cost: 127,000 dollars. The bars representing the Vocational training read, Income asterisk: 35,720 dollars; Cost: 33,000 dollars. The bars representing H. S. Diploma read, Income asterisk: 30,000 dollars and 0 dollars below. The asterisk reads, Average annual income for entry level position. The source below reads, Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2012.

The fourth section shows a world map. An illustration of many stick figures holding hands are shown and a dotted line points toward the United States. A text below the illustration reads, Even though jobs are increasingly being outsourced to other countries, demand for high-precision skills is at an all time high in the U. S. Most of the jobs you’ll get with a Trade School education require a physical presence making them extremely difficult to export to another country.

A text below reads, For more information and other education resources visit The simple dollar dot com. Another text below reads, The simple dollar. Logos of Facebook, Twitter, and Pinterest read, w w w dot facebook dot com slash the simple dollar; at the rate of the simple dollar; w w w dot pinterest dot com slash the simple dollar, respectively.

![]()

READING ARGUMENTS

1. This visual is from a personal finance website and blog called The Simple Dollar. The site focuses on practical financial advice: eliminating debt, choosing a financial strategy, banking, and budgeting. How might the purpose of the site—and the nature of its audience—influence how the writers evaluate educational choices?

2. While this is a visual argument, it also requires a fair amount of reading. Are all these words necessary? Do you find the textual element of the graphic accessible and effective?

3. This visual has four different sections. Which is the strongest, or provides the best support for the main argument? Which element is the weakest? Explain.

![]()

AT ISSUE: SHOULD EVERY AMERICAN GO TO COLLEGE?

1. In paragraph 5 of his essay, Hoover cites a Pew Research Survey that asked college graduates about the main purpose of college: “Forty-seven percent said ’to teach knowledge and skills that can be used in the workplace,’ 39 percent said ’to help an individual grow personally and intellectually,’ and 12 percent said ’both equally.’ ” How would you answer this question about the main purpose of college?

2. In paragraph 5 of his essay, J. D. Vance writes: “A host of professions—photographers, lab technicians, and equipment operators—have seen their ranks swell with college graduates, despite the absence of any obvious need for forklift drivers to have studied Michel Foucault.” How do you think that Andre Perry would respond to this claim?

3. Murray bases his argument on the IQ, or “intelligence distribution” (para. 1), among the general population. What are the strengths and weaknesses of his focus on IQ?

![]()

WRITING ARGUMENTS: SHOULD EVERY AMERICAN GO TO COLLEGE?

1. After reading and thinking about the four essays in this casebook, do you think more people should be encouraged to attend college, or do you think some people should be discouraged from doing so? Do you see higher education as a “right” (and a necessity) for most, or even all citizens? Write an argumentative essay in which you answer these questions.

2. Based on your own observations as well as the essays in this chapter, what is the biggest challenge—or challenges—that most students face as they make their way through a postsecondary education?