Practical argument: A text and anthology - Laurie G. Kirszner, Stephen R. Mandell 2019

Casebook: How should we solve the opioid problem?

Debates, casebooks, and classic arguments

In her essay “The Myth of What’s Driving the Opioid Crisis” (p. 672), psychiatrist Sally Satel argues that our dominant narrative for explaining this epidemic is misleading. Regardless of the epidemic’s various causes or storylines, however, few dispute that it is a serious problem. The crisis has its roots in the 1990s, when doctors began taking a greater interest in pain management. With some encouragement from the pharmaceutical industry, physicians began prescribing the newly developed oxycodone, a powerful, semisynthetic painkilling opiate. Some doctors began overprescribing opiates or writing long-term prescriptions for these highly addictive medications when perhaps only a few doses were needed to deal with a patient’s short-term pain. In some cases, addicted patients moved from prescription drugs to illicit substances, such as heroin and fentanyl. The effects have been staggering. According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), 700,000 people died from drug overdoses between 1999 and 2017; on average, 130 Americans die daily from opioid overdoses. Such statistics, of course, do not reflect the economic and emotional toll the epidemic has taken on the many individual communities and families that have been devastated by opiates.

Health experts, politicians, and the general public all recognize the problem, and the president has designated it a national emergency. In fact, at a time of intense political polarization, this is one substantive issue that Americans of all political leanings agree needs to be addressed. But the question remains: How? Not surprisingly, government regulators, medical associations, and doctors have worked to restrict prescriptions for these drugs as well as to reduce their proliferation. The CDC has released more stringent guidelines on how and when to dispense opioids. Law-enforcement agencies have worked to make their responses to the crisis more effective and humane. In the private sector, churches and other organizations have also tried to help address the issue in their communities, and in the United States as a whole. So far, however, the crisis persists.

The four writers represented in this casebook all provide informed insight into the problem even as they approach its complexity from different points of view. For Ericka Andersen (“The Opioid Epidemic Is a Cultural Problem. It Requires Cultural Solutions.”), top-down solutions, which rely on government intervention and regulation are not the answer. In “The Solution to the Opioid Crisis,” Stanton Peele argues that our current conventional wisdom about the crisis—offered by public health officials like the U.S. Surgeon General—is useless, at best. He urges a radical rethinking of the problem—as well as a reframing of the model of addiction as a “disease.” Peter Moore (“The Other Opioid Crisis”) addresses an entirely different aspect of the opioid problem: the plight of chronic pain sufferers who cannot get the medications that they need to alleviate their pain. Finally, in “The Myth of What’s Driving the Opioid Crisis,” Sally Satel offers a comprehensive critique of our culture’s current understanding of the problem and suggests some possible remedies.

THE OPIOID EPIDEMIC IS A CULTURAL PROBLEM. IT REQUIRES CULTURAL SOLUTIONS.

ERICKA ANDERSEN

This essay was published in the Washington Examiner on August 21, 2018.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced last week that drug overdose deaths rose to 72,000 in 2017, a 10 percent increase from 2016. This is more than the number of people who die each year from car crashes or suicides.

Overdose deaths are now close to the 7th leading cause of death in this country, responsible for 1.5 percent of all deaths.

The national numbers mask even bigger spikes in some states. In Indiana, overdose rates increased by 17 percent in 2017, one of the largest increases the nation has seen.

The spike in overdose deaths will result in renewed calls to regulate opioids, which are responsible for two-thirds of overdose deaths. Already, nearly three-quarters of Americans believe the government should do more to address the problem, according to a CBS poll from earlier this year.

But the overdose crisis is a cultural problem that doesn’t necessarily respond to government solutions. As regulations surrounding prescription painkillers tighten, more dangerous black market opioids like fentanyl have taken their place. Deaths by such synthetic opioids increased by one-third last year, according to the CDC.

Rather than doubling down on top-down initiatives like pharmaceutical restrictions and the drug war, policymakers and concerned citizens should focus on fostering bottom-up cultural change through local community support, church programs, awareness campaigns, and free access to recovery programs.

People don’t stop using drugs because doctors and pharmacists curb prescriptions or because police step up enforcement. They stop using drugs because they find a greater purpose, a supportive community, and a reason to live beyond the high.

Projects like Back on My Feet, where I was a volunteer leader for several years, use running as a means to help recovering addicts overcome. I remain friends with at least one man from the program who has retained his sobriety for more than 7 years now.

Another example is The Phoenix, a gym whose only membership requirement is 48 straight hours of sobriety and offers a vital community aspect so many addicts are missing in their lives. Studies show that regular exercise may help in preventing drug addiction, due to the natural release of dopamine that is similar to that of a manufactured high.

“Government efforts to regulate opioid prescription may even exacerbate the epidemic.”

You can also look to things like local YMCAs and community centers, which foster community engagement in a healthy way that promotes friendship, camaraderie, and purpose. Additionally, new churches in small communities attract individuals who had never attended church or hadn’t attended in many years. It’s clear there is a strong desire for this kind of life support, and yet it won’t ever be the main focus for combating addiction in the media or on Capitol Hill.

Policymakers should prioritize funding these types of programs and promote more personalized kinds of help that has a lasting impact and addresses the root of the issue, rather than one of access and regulation. Empowerment of local communities to help their citizens where they are is a far better way than national regulations that consider all victims of addiction to require the same solutions.

Government efforts to regulate opioid prescription may even exacerbate the epidemic by forcing those in pain onto the black market to use far more dangerous and unregulated opioids. “The focus on prescription painkillers is especially misguided now that the vast majority of opioid-related deaths actually involve illegally produced drugs,” said veteran journalist on the issue, Jacob Sullum.

I speak with the conviction of the converted. On a recent radio show, where I discussed my support for government initiatives to regulate the pharmaceutical industry, a distressed caller educated me about her sister. She lives with chronic pain and is now unable to get the appropriate amount of painkillers she needs to control it. Her misery made me rethink my original support for tackling the crisis through regulations that put limits on drugs based on arbitrary quantities.

Adam Trosell of Pittsburgh, who has lived with chronic pain for 15 years and has been unable to find a doctor to prescribe the opioids that had been providing him relief, noted that the depression that comes with chronic pain is horrific. He says government efforts to overregulate are “inhumane and cruel” to people like him. In the most extreme cases, some in chronic pain who are unable to access painkillers because of well-intended government regulations are considering or committing suicide.

As last week’s overdose data demonstrates, government regulation is not curbing the overdose epidemic. Cultural organizations like Back on My Feet, The Phoenix, and local community centers are more powerful, long-lasting solutions for addicts. Policymakers should give these a fresh look before doubling down on failed prohibition policies.

![]()

READING ARGUMENTS

1. Beyond introducing the topic, what do the first three paragraphs of this essay accomplish?

2. Where does Andersen introduce appeals to ethos? Do you find these appeals persuasive? Why or why not?

3. Where does Andersen use a cause-and-effect argument? In what sense is this essay a proposal argument?

4. According to Andersen, government efforts to regulate opioids may actually make the problem worse. Why?

5. Andersen makes several broad claims in paragraph 11. Does she support these claims with evidence? Explain.

THE SOLUTION TO THE OPIOID CRISIS

STANTON PEELE

This article first appeared in Psychology Today on March 6, 2017.

Here’s What We Must Do to Improve Our Addictive Situation

In 2016, the American Surgeon General, Vivek Murthy, announced in a new report on addiction, as though he had just discovered the structure of DNA, “Addressing the addiction crisis in America will require seeing addiction as a chronic illness, not as a moral failing. Addiction has been a challenge for a long time, but we finally have the opportunity and the tools to address it.” At last, we’re ready to solve addiction!

Murthy has lately been joined by such medical and social luminaries (both of whom I admire) as Atul Gawande and J.D. Vance.

Instead of presenting solutions, however, Murthy simply rehashed our tried-and-failed American bromides. In their place, I outline the actual strategies, almost the reverse of what he is proposing, to solve our addiction crisis.

Murthy’s Bromides

1. Scare People (Even More!) about Opioid “Overdoses.”

If people were to consume pure doses of heroin or other opioids, their likelihood of accidental death is reduced to nearly naught. Yet the myth that people typically develop an inordinate, insatiable desire for a single drug—when in fact those most at risk are mixing a variety of substances in what can be considered either a chaotic pattern or an abandoned, intentionally self-destructive one—still fatally misinforms our policies.

2. Convince People That Drugs Cause Addiction.

The headline news from the Surgeon General’s report: “1 in 7 in USA will face substance addiction.” “We underestimated how exposure to addictive substances can lead to full blown addiction,” Murthy told NPR. “Opioids are a good example.” Note to the Surgeon General: The definitive U.S. psychiatric guide, DSM-5, no longer applies the term “addiction” to any substances, but only to non-drug activity. How he rationalizes his perspective that drugs have an insufficiently recognized special quality of addiction with the DSM-approved possibility of becoming addicted to gambling, or the non-DSM-approved but still-real possibility of becoming addicted to sex, love, the internet, or any other compelling involvement, is anyone’s guess.

Addiction is not in the thing. Addiction is in the life. And when addiction is understood as being steeped in people’s lives, we recognize that myriad drug or non-drug experiences are liable to become compulsively destructive. The thrust of Murthy’s thinking—an impetus to further restrict access to certain drugs—is as flawed conceptually as it is unachievable practically.

3. Emphasize “Prevention”—Meaning Avoiding Substance Use Altogether.

“The earlier people try alcohol or drugs,” says the surgeon general’s report, “the more likely they are to develop a substance use disorder.” Prevention, to Murthy et al., means prevention of drug use, as opposed to what it should mean: prevention of addiction or death.

These U.S. statistics are meaningless when considered outside of people’s life context in America, a context I provide in my book, Addiction-Proof Your Child.

Consider that in Southern Europe, where people begin drinking legally at much younger ages (typically 16), rates of problematic drinking are far lower than in the U.S. and other temperance (Northern European and English-language) countries. Consider that in the U.S., given restrictions on the use of alcohol and other drugs, people’s first experiences with them are likely to be binge episodes with their peers, rather than moderate use with older, experienced family members. Consider that despite “Just Say No” being repeated to kids for decades, 40 percent have used marijuana by the time they leave high school, and 33 percent have drunk alcohol in the last 30 days—the majority of whom, critically, have engaged in binge-drinking. Both of the numbers rise rapidly following high school and into people’s early 20s.

Simply teaching people not to use drugs has gotten us where we are today.

4. Hype Supposed Biological Causes of Addiction and Minimize Social Causes.

“We now know from solid data that substance abuse disorders don’t discriminate,’’ Murthy told NPR. “They affect the rich and the poor, all socioeconomic groups and ethnic groups. They affect people in urban areas and rural ones.”

This is quite wrong. Addiction does affect people from all backgrounds, but not at equal rates. It does discriminate. As discussed by Maia Szalavitz:

“Addiction rates are higher in poor people—not because they are less moral or have greater access to drugs, but because they are more likely to experience childhood trauma, chronic stress, high school dropout, mental illness, and unemployment, all of which raise the odds of getting and staying hooked.”

Murthy instead pursues a line of thinking, our neurochemical revolution, that has yet to produce a single meaningful diagnostic or treatment tool: “Now we understand that these disorders actually change the circuitry in your brain. They affect your ability to make decisions, and change your reward system and your stress response. That tells us that addiction is a chronic disease of the brain.”

Murthy’s misdirection supports our heavily funded medical efforts to thwart addiction while we ignore the critical social levers for reversing our addiction epidemic—an approach that would instead require major social change to address the havoc in poor urban and rural communities that turns them into addiction hubs.

5. Expand Our Drug Treatment Industry and Addiction Support Groups.

“We would never tolerate a situation where only one in 10 people with cancer or diabetes gets treatment, and yet we do that with substance-abuse disorders,” said Murthy, speaking of an estimated 20.8 million Americans with these disorders.

Contrary to this perceived shortfall, no other country in the world provides as much disease-oriented addiction treatment (i.e., 12-step and vaguely biomedical treatment—“vaguely” since no treatments actually directly address supposed brain centers of addiction) as does the US. Yet North America, as a global harm reduction report notes, has the “highest drug-related mortality rate in the world.”

Research repeatedly demonstrates that those addicted to drugs regularly solve their addictions given supportive life conditions. In fact, the large majority of dependent drug users reverse addiction on their own—most who ever qualify for a substance use disorder diagnosis move past it by their mid-30s.

How are we providing so much treatment with such bad outcomes? This is because we are incapable of acknowledging that most addiction treatment is no more effective than the ordinary course of the “disease.” And, thus, we can’t focus on what about people’s lives enables them to recover, and to encourage these conditions, rather than thrusting more and more people into treatment.

I Would Remedy (Well, Improve) America’s Drug and Addiction Problems

What, instead, are the messages that the U.S. surgeon general should be spreading?

1. Loudly advertise the dangers of drug-mixing. Spread this message widely, including in schools, along with other critical information about drugs, while teaching drug-use and life skills.

2. Call for legal regulation of heroin and other currently illegal drugs to protect users from unwittingly consuming the haphazard, fraudulent, and dangerous combinations often sold on the street. Call for painkillers to be available to people who want them under medical supervision, along with heroin maintenance sites, while making medical or other trained supervision of use available.

It is worth noting here that just as the Surgeon General’s addiction report came out, the British Medical Journal (BMJ) issued a clarion call: “The war on drugs has failed: doctors should lead calls for drug policy reform.” The BMJ’s report does not contain the words “brain,” “disease,” or “addiction.” Instead, it asserts:

“. . . a thorough review of the international evidence concluded that governments should decriminalize minor drug offenses, strengthen health and social sector approaches, move cautiously towards regulated drug markets where possible.”

3. The SG’s report does note the usefulness of medication-assisted treatment including drugs like methadone and buprenorphine to assist in quitting heroin with greatly reduced risk, but fails to recognize that, time and again, medications like naltrexone and baclofen are insufficient in themselves, and hardly improve overall outcomes, in quitting a drug or alcohol addiction.

4. Demand the full-scale deployment of other harm reduction services and supplies, from naloxone (Narcan) to syringe access to supervised drug consumption rooms—an expansion that will not only save many lives, but also do far more to reduce the stigmatization of people who use drugs than the empty words in the current report.

“We must normalize and rationalize the reality of our drug use.”

5. Make clear that addiction is not a disease and therefore, that it is escapable and not a lifelong identity. Instead, point out, it is a phenomenon driven by psychological and social factors, and therefore inseparable from the realities of people’s daily lives. Publicly tell politicians that if they really care about reducing addiction, taking meaningful steps to address inequality and absence of opportunity and to rebuild meaningful community would be the single best thing they could do.

6. Declare that we must abandon the futile goal of a drug-free society, which decades of efforts and billions of dollars have been unable to accomplish. Instead, recognize that we are all drug users—from caffeine and alcohol to prescribed medications to commonplace Adderall use by students. Affirm that drugs are a normal part of human experience, that they provide benefits, and that they are even enjoyed—despite their potential dangers. This is how we approach experiences and involvements—from driving to love and sex—that can have dangerous or overwhelming effects. It’s how alcohol is used throughout Southern Europe—indeed, this is how the large majority of Americans who drink think about alcohol.

Radical as this is to American ears, we must normalize and rationalize the reality of our drug use—as opposed to encouraging uncontrolled and chaotic use of drugs while simultaneously vilifying and demonizing them.

As Murthy’s report trumpets by way of perversely recommending more of what has long failed us: An American dies every 19 minutes from narcotics-related drug use. Or, as Gawande points out, more Americans now die of overdoses (they’re not overdoses, see above) than died of AIDS at the peak of that epidemic. He recommends better prescription practices—which is a lot like proposing tax (or health care) reform. After it passes (if it does pass) the new system is immediately assailed for a whole new host of problems.

Vance simply announces in his New York Times op-ed that he is “founding an organization to combat Ohio’s opioid epidemic,” but doesn’t offer a single opioid-related solution. Actually, Vance’s book Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis, shows that purpose and community are the cure—just as their absence is the problem. Let’s hope that Vance, a moral and brilliant man, is able to affect these critical factors in Ohio, setting a model for proceeding elsewhere.

But what we really need is a whole new way of thinking.

![]()

READING ARGUMENTS

1. In his third paragraph, Peele criticizes former Surgeon General Vivek Murthy for his response to the opioid crisis: “Instead of presenting solutions, . . . Murthy simply rehashed our tried-and-failed American bromides.” What is a bromide? What connotation does the word have? According to Peele, what are some of the specific problems with Murthy’s suggestions?

2. How does Peele use definition to criticize Murthy’s proposals—and to further his own argument?

3. According to Peele, what is the relationship between socioeconomic class and addiction? Why is it important to recognize the relationship?

4. The “disease model” has long been used to explain addiction. Peele argues, however, that we must make clear that addiction is not a disease. Why? What problems does he identify with that view?

5. Peele argues, “Radical as this is to American ears, we must normalize and rationalize the reality of our drug use—as opposed to encouraging uncontrolled and chaotic use of drugs while simultaneously vilifying and demonizing them” (para. 27). Do you agree? Why or why not?

THE OTHER OPIOID CRISIS

PETER MOORE

This article appeared in Prevention magazine on February 1, 2018.

Lauren Deluca had never thought much about her pancreas until it attacked her. One day in 2015, she felt searing abdominal pain that worsened when she ate. “It was like the scene in Alien,” she recalls—the one where an extraterrestrial creature erupts from a space traveler’s abdomen. The flare-ups were worst after meals, when they sometimes also included nausea and vomiting. Her doctors were initially stumped in their efforts to diagnose the otherwise healthy 35-year-old, even as her pain worsened. She made repeated trips to the emergency room, where she engaged a series of doctors in an attempt to understand what was wrong and to secure prescription opioids to help her cope.

Unfortunately for Deluca, her quest bore the marks of doctor shopping, a term for the way in which people addicted to opioids accumulate overlapping prescriptions to feed their cravings. Deluca says she was doing nothing of the sort but feels she was blackballed in her pursuit of treatments—of any kind—that would help her survive her workdays as a business insurance broker in Worcester, MA.

She was eventually diagnosed with chronic pancreatitis, in which the organ repeatedly becomes inflamed and sustains irreversible damage during acute attacks. As the disease ran its course, she lost 11 percent of her pancreatic function, vital for digestion, and dropped 20 lb from an already lean frame. She’s 37 now but says she feels older: Pain wears the body down.

Curbing a Crisis

In the past few years, the United States has grappled with the widespread use of opioids, a class of drugs that includes prescription oxycodone (Oxycontin) and hydrocodone with acetaminophen (Vicodin), as well as illegal versions like heroin.

In 2015 alone, nearly 92 million people in the US—both prescription drug users and illegal users—took opioids for various ailments, for both short and long periods. About 13 million of these people misused them—by obtaining and taking them illegally or by taking prescribed drugs they no longer needed—according to a report published in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

As the opioid crisis has mushroomed, these users typically seek out the drugs on the street or switch to illegal drugs like heroin and fentanyl when their access to a prescription ends. This has led to fatal overdoses in numbers that keep ticking alarmingly upward: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention tallied more than 200,000 fatal overdoses between 1999 and 2016; there were another 42,000 in 2016 alone, and the numbers were still rising in 2017. As a result, federal and state governments have cracked down on the drugs’ availability, often by restricting the quantities doctors can prescribe.

The new policies are choking off access to the medications for some of the 87.5 million chronic-pain patients who take them according to their prescriptions and don’t misuse them. Like Deluca, these people rely on regular access to often-modest doses of the medications to live productive lives. The “solution” to the opioid crisis—making the drugs scarcer—has, in effect, created a new kind of medical emergency, leaving people cut off from necessary medicine and cast under a cloud of suspicion.

Terri Lewis is a clinical specialist in rehabilitation and mental health in Tennessee, a hotbed of opioid overdoses, who advocates for chronic-pain patients trying to find treatment and medication support. Lewis is also a prominent expert on patient abandonment, in which chronic-pain patients lose access to doctors concerned about running afoul of government-mandated restrictions. “It is a catastrophic situation,” she says. “People are being cut off cold turkey by their doctors. They have no health care, they have no physician, and they have nowhere to go.”

That includes Deluca, whose home state imposed strict regulations on opioid prescriptions the year before she suffered her first pancreatic attack. She wasn’t about to try to buy them illegally. She finally received medication from a doctor last December, but the dosage is too low, and she’s still struggling to recover from the damage sustained when she was denied care. Now she manages the best she can—and has become an advocate for change.

Pain and Prescriptions

Until the early 1990s, pain was barely recognized as a symptom and, hence, largely ignored—at least by doctors. Patients didn’t have that luxury. They enrolled in the “bite on a stick” school of pain remediation, says Mary Lynn McPherson, a professor of palliative care at the University of Maryland.

Then, in the 1990s, the pain-treatment pendulum swung in favor of drug interventions with the advent of powerful synthetic medications such as Oxycontin. These new drugs gave patients levels of relief they had not experienced previously. Urged along by “education” programs sponsored by the pharmaceutical industry, primary care physicians began prescribing them in greater quantities.

What doctors didn’t necessarily account for: Pain comes in many forms. There is acute pain, the kind you feel when you break a bone. Strong drugs can blunt the effects of that sort of trauma. Then there’s chronic pain, which can result from a wrenched back, a botched surgery, a degenerative condition—and which delivers such a payload of hurt that it can rewire the body’s nervous system. The American Chronic Pain Association lists more than 120 maladies that can cause persistent pain, without counting the likes of sports injuries or dental abscesses. Chronic pain affects more than 100 million adults, according to the National Academy of Sciences.

Sometimes, even after the injury or disease heals, the agony continues. And when the pain lasts, the drugs often have to, too—which is not ideal when the most-prescribed medicines also hold a grave risk of addiction. Patients in these situations can safely take carefully calibrated doses of opioids at levels that don’t trigger addiction for decades, says Richard W. Rosenquist, chair of pain management at Cleveland Clinic. People’s reactions to the drugs are unique to them. Those who have constant, chronic pain take medication more frequently just to get through their days, and these patients are more likely to develop a tolerance and need higher doses. Others take low-strength doses only when they expect flare-ups. The key is to match the dosage to the patient.

An Overreaching Crackdown

But when the new category of opioids came out, some doctors prescribed them in large quantities to sufferers of all kinds of pain. Pharmaceutical companies marketed them aggressively and played down the risk of addiction, according to the American Journal of Public Health. For a broken bone, opioids are meant to provide short-term help, says Sameer Awsare, an internist at Kaiser Permanente Santa Clara Medical Center in California. “If it will hurt for only 2 or 3 days, you should get 10 pills, not 200 pills, which is what ended up happening,” he says. “People got addicted and took more.”

That’s how a limited, but effective, medicine became a scourge. The United States makes up 4.6 percent of the world’s population; 80 percent of all opioids are consumed here, including 99 percent of the hydrocodone, says Awsare.

As the number of overdoses grew, all 50 states launched legislative assaults on the problem, including seven that declared public health emergencies. (Massachusetts was the first, in 2014.) They mandated rollbacks in the number and duration of opioid prescriptions, established registries of users, began monitoring pharmacies, and closely watched and placed restrictions on doctors who were prescribing the drugs. In addition to doctor shopping, the term pill mill (a clinic that is loose with prescriptions) entered the lexicon. Last August, President Donald Trump declared the opioid crisis a national emergency, pledging funds and extra enforcement (with no tangible results to date beyond the measures already in place).

Predictably, opioids taken under any circumstance were swept up in the panic around illegal use. According to the CDC, 40 million fewer opioid prescriptions were written in 2016 than 2 years earlier, the lowest rate in more than a decade. But opioid-related deaths continue to soar, largely because of an influx of street drugs that have effects that are similar to those of the medication. And the pressure on doctors to curb prescriptions remains intense. “When you’re a prescriber and the Drug Enforcement Administration is breathing over your shoulder,” says the University of Maryland’s McPherson, “you think, Uh-huh, this is what I have to do.”

Caught in the Middle

As a result of the crackdown, fewer doctors will even take a pain patient’s appointment. Steven Wright, a physician who is also vice president of the Colorado Pain Society, quit seeing patients 3 years ago. “I was becoming an administrator of a drug-reduction plan rather than a clinician making decisions about the best thing for the patient,” he says.

This confluence of events leaves people like Zoe Haigh in a significant bind. Haigh, 44, of Danville, CA, suffered a congenital hip dislocation as an infant that wasn’t discovered until she was 3 years old. She experiences “bone rubbing on bone” whenever she moves and has taken opioids for everyday pain since she was a child. She also takes hydromorphone (Dilaudid) and extended-release morphine (Kadian) when she’s going to be active and fentanyl lozenges when she’s in agony.

The opioid crisis has turned her into a suspected addict, she says. Bowing to new restrictions, her doctor cut off her prescription last November, Haigh says. Making things worse, she felt a social stigma on top of her pain. “I was made to feel ashamed and a pariah for following my doctor’s orders,” she says.

Pain sufferers who can’t get medication face the prospect of leading diminished lives. Barbara Obstgarten, 69, an avid crafter from Long Island, NY, had a 2008 knee replacement surgery that she says “went horribly wrong.” Her doctor went on vacation after the operation, and her rehabilitation was unsupervised. She never recovered full use of her knee, and the pain has persisted ever since.

“For many, the prospect of being cut off triggers despair.”

She takes hydrocodone with acetaminophen (Norco) and tramadol to get through the Christmas craft fair season and to handle flare-ups. “The day is going to come when some of my doctors will not give them to me,” she says. “I’ve already had one internist, whom I had a good relationship with for 30 years, tell me he won’t give me a prescription.”

For many, the prospect of being cut off triggers despair. Wright, of the Colorado Pain Society, cites a survey of 3,400 pain patients, doctors, and other health care providers by the International Pain Foundation. Since the CDC guidelines for opioid dosing came out, 84 percent of US patients surveyed said they were experiencing more pain, and 42 percent admitted they were considering suicide due to their predicament.

It’s no idle threat. Cathy Kean is a California pain patient and advocate who maintains a database of fellow sufferers who have taken their own lives. Her list—with references and personal histories—has 17 names. “I am fighting for my life,” Kean says. “But more than that, I’m fighting for the veteran who has a gun to his head because he’s in so much pain and feels nobody cares or will listen.”

The Battle for Access

Advocates like McPherson, of the University of Maryland, believe that health care providers, including physicians, need to be skilled in pain management so they can minimize the risks. As Kristen Silvia, a rehabilitative specialist at the Maine Medical Partners in Portland, points out, there is ample evidence that asking questions about childhood trauma and family history of drug and alcohol abuse can help identify potential misusers. That could leave most patients, who are at less risk, free to access drugs that help them. And more research is needed to identify the best method for weaning patients off opioids, which currently isn’t well understood.

Kean and others are calling for federal and state governments to adopt more-nuanced policies and studies on the effects of opioids. Lauren Deluca, the pancreatitis patient, has formed a national nonprofit—the Chronic Illness Advocacy and Awareness Group (ciaag.net)—and taken lobbying trips to Washington, DC, to advocate for people like her. Her organization is pushing for the creation of “intractable pain” cards, similar to ones now issued for medical marijuana, that document the need for opioids. Says Deluca: “We are looking to put our medical care back into the hands of qualified physicians and get the DEA and Department of Justice out of our doctors’ offices.”

Stefan Kertesz, an addiction scholar and general internist at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, recently spearheaded a petition submitted to the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA), the nation’s top health care accreditation organization, signed by 80 practitioners concerned about harm the restrictions are causing their patients. The petition asks the NCQA to avoid taking action that would push doctors to prescribe lower doses to stable patients. Last June, Kertesz presented a talk urging the CDC to clarify guidelines that have been widely misapplied, resulting in reduced dosages for all patients. Some regulators have told him they’re aware of these issues, Kertesz says.

For people who are in pain every day, a new way of handling the opioid epidemic—one with greater nuance that accommodates people with genuine needs—can’t come soon enough.

![]()

READING ARGUMENTS

1. According to Moore, how many Americans took opioids—both legally and illegally—in 2015?

2. Before the 1990s, how was pain viewed and dealt with by doctors and others in the medical profession? What changed in the 1990s?

3. Moore includes anecdotal evidence in the form of personal stories about people suffering from pain. Do you find this evidence credible and persuasive? Why or why not?

4. What do you think Moore’s purpose in writing this essay was? To inform? To persuade? To inspire some kind of action? Explain.

THE MYTH OF WHAT’S DRIVING THE OPIOID CRISIS

SALLY SATEL

This article was published by the online magazine Politico on February 21, 2018.

As an addiction psychiatrist, I have watched with serious concern as the opioid crisis has escalated in the United States over the past several years, and overdose deaths have skyrocketed. The latest numbers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show fatalities spiraling up to about 42,000 in 2016, almost double the casualties in 2010 and more than five times the 1999 figures. The White House Council of Economic Advisers recently estimated that the opioid crisis cost the nation half a trillion dollars in 2015, based on deaths, criminal justice expenses, and productivity losses. Meanwhile, foster care systems are overflowing with children whose parents can’t care for them, coroners’ offices are overwhelmed with bodies, and ambulance services are straining small-town budgets. American carnage, indeed.

I have also watched a false narrative about this crisis blossom into conventional wisdom: The myth that the epidemic is driven by patients becoming addicted to doctor-prescribed opioids, or painkillers like hydrocodone (e.g., Vicodin) and oxycodone (e.g., Percocet). One oft-quoted physician refers to opioid medication as “heroin pills.” This myth is now a media staple and a plank in nationwide litigation against drugmakers. It has also prompted legislation, introduced last spring by Senators John McCain and Kirsten Gillibrand—the Opioid Addiction Prevention Act, which would impose prescriber limits because, as a news release stated, “Opioid addiction and abuse is commonly happening to those being treated for acute pain, such as a broken bone or wisdom tooth extraction.”

But this narrative misconstrues the facts. The number of prescription opioids in circulation in the United States did increase markedly from the mid-1990s to 2011, and some people became addicted through those prescriptions. But I have studied multiple surveys and reviews of the data, which show that only a minority of people who are prescribed opioids for pain become addicted to them, and those who do become addicted and who die from painkiller overdoses tend to obtain these medications from sources other than their own physicians. Within the past several years, overdose deaths are overwhelmingly attributable not to prescription opioids but to illicit fentanyl and heroin. These “street opioids” have become the engine of the opioid crisis in its current, most lethal form.

If we are to devise sound solutions to this overdose epidemic, we must understand and acknowledge this truth about its nature.

For starters, among people who are prescribed opioids by doctors, the rate of addiction is low. According to a 2016 national survey conducted by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), 87.1 million U.S. adults used a prescription opioid—whether prescribed directly by a physician or obtained illegally—sometime during the previous year. Only 1.6 million of them, or about 2 percent, developed a “pain reliever use disorder,” which includes behaviors ranging from overuse to overt addiction. Among patients with intractable, noncancer pain—for example, neurological disorders or musculoskeletal or inflammatory conditions—a review of international medical research by the Cochrane Library, a highly regarded database of systemic clinical reviews, found that treatment with long-term, high-dose opioids produced addiction rates of less than 1 percent. Another team found that abuse and addiction rates within 18 months after the start of treatment ranged from 0.12 percent to 6.1 percent in a database of half a million patients. A 2016 report in the New England Journal of Medicine concluded that in multiple published studies, rates of “carefully diagnosed” addiction to opioid medication averaged less than 8 percent. In a study several years ago, a research team purposely excluded chronic-pain patients with prior drug abuse and addiction from their data, and found that only 0.19 percent of the patients developed abuse and addiction to opioids.

“For starters, among people who are prescribed opioids by doctors, the rate of addiction is low.”

Indeed, when patients do become addicted during the course of pain treatment with prescribed opioids, often they simultaneously face other medical problems such as depression, anxiety, other mental health conditions, or current or prior problems with drugs or alcohol. According to SAMHSA’s 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, more than three-fourths of those who misuse pain medication already had used other drugs, including benzodiazepines and inhalants, before they ever misused painkillers. And according to CDC data, at least half of all prescription opioid-related deaths are associated with other drugs, such as benzodiazepines, alcohol, and cocaine; combinations that are often deadlier than the component drugs on their own. The physical and mental health issues that drive people to become addicted to drugs in the first place are very much part of America’s opioid crisis and should not be discounted, but it is important to acknowledge the influence of other medical problems and other drugs.

Just because opioids in the medical context don’t produce high rates of addiction doesn’t mean doctors aren’t overprescribing and doing serious harm. The amount of opioids prescribed per person in 2016, though a bit lower than the previous year, was still considered high by the CDC—more than three times the amount of opioids dispensed in 1999. Some doctors routinely give a month’s supply of opioids for short-term discomfort when only a few days’ worth or even none at all is needed. Research suggests that patients given post-operation opioids don’t end up needing to use most of their prescribed dose.

In turn, millions of unused pills end up being scavenged from medicine chests, sold or given away by patients themselves, accumulated by dealers, and then sold to new users for about $1 per milligram. As more prescribed pills are diverted, opportunities arise for nonpatients to obtain them, abuse them, get addicted to them, and die. According to SAMHSA, among people who misused prescription pain relievers in 2013 and 2014, about half said that they obtained those pain relievers from a friend or relative, while only 22 percent said they received the drugs from their doctor. The rest either stole or bought pills from someone they knew, bought from a dealer or “doctor-shopped” (i.e., obtained multiple prescriptions from multiple doctors). So diversion is a serious problem, and most people who abuse or become addicted to opioid pain relievers are not the unwitting pain patients to whom they were prescribed.

While reining in excessive opioid prescriptions should help limit diversion and, in theory, suppress abuse and addiction among those who consume the diverted supply, it will not be enough to reduce opioid deaths today. In the first decade of the 2000s, the opioid crisis almost seemed to make sense: The volume of prescribed opioids rose in parallel with both prescription overdose deaths and treatment admissions for addiction to prescription opioids. Furthermore, 75 percent of heroin users applying to treatment programs initiated their opioid addiction with pills, so painkillers were seen as the “gateway” to cheap, abundant heroin after their doctors finally cut them off. (“Ask your doctor how prescription pills can lead to heroin abuse,” blared massive billboards from the Partnership for a Drug-Free New Jersey.) If physicians were more restrained in their prescribing, the logic went, fewer of their patients would become addicted, and the pipeline to painkiller addiction and ultimately to heroin would run dry.

It’s not turning out that way. While the volume of prescriptions has trended down since 2011, total opioid-related deaths have risen. The drivers for the past few years are heroin and, mostly, fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that is 50 times as potent as heroin. Fentanyl has legitimate medical use, but there is also illicit fentanyl, trafficked mostly from China, often via the Dark Web. Fentanyl and heroin (which itself is usually tainted to some extent with the fentanyl) together were present in more than two-thirds of all opioid-related deaths in 2016, according to CDC data. Painkillers were present in a little more than one-third of opioid-related deaths, but a third of those painkiller deaths also included heroin or fentanyl. While deaths from prescription opioids have basically leveled off, when you look at deaths in which prescription opioids plus heroin and fentanyl were present, then the recorded deaths attributed to prescription opioids continue to climb, too. (An especially pernicious element in the mix is counterfeiters with pill presses who sell illicit fentanyl in pill form deceptively labeled as OxyContin and other opioid pain relievers or benzodiazepines.)

Notably, more current heroin users these days seem to be initiating their opioid trajectory with heroin itself—an estimated 33 percent as of 2015—rather than with opioid painkillers. In the first decade of the 2000s, about 75 to 80 percent of heroin users started using opioids with pills (though not necessarily pain medication prescribed by a doctor for that particular person). It seems that, far more than prescribed opioids, the unpredictability of heroin and the turbocharged lethality of fentanyl have been a prescription for an overdose disaster.

Intense efforts to curb prescribing are underway. Pharmacy benefit managers, such as CVS, insurers, and health care systems have set limits or reduction goals. Statebased prescription drug monitoring programs help doctors and pharmacists identify patients who doctor-shop, ER hop, or commit insurance fraud. As of July, 23 states had enacted legislation with some type of limit, guidance, or requirement related to opioid prescribing. McCain and Gillibrand’s federal initiative goes even further, to impose a blanket ban on refills of the seven-day allotment for acute pain. And watchdog entities such as the National Committee for Quality Assurance have endorsed a system that compares the number of patients receiving over a certain dose of opioids with the performance rating for a physician.

A climate of precaution is appropriate, but not if it becomes so chilly that doctors fear prescribing. This summer, a 66-year-old retired orthopedic surgeon who practiced in Northern California—I’ll call her Dr. R—contacted me. For more than 30 years, she had been on methadone, a legitimate opioid pain medication, for an excruciating inflammatory bladder condition called interstitial cystitis. With the methadone, she could function as a surgeon. “It gave me a life. I would not be here today without it,” she told me. But one day in July, her doctor said the methadone had to stop. “She seemed to be worried that she was doing something illegal,” Dr. R told me.

Dr. R was fortunate. She found another doctor to prescribe methadone. But her experience of nonconsensual withdrawal of opioids is not isolated. Last year, the nonprofit Pain News Network conducted an online survey among 3,100 chronic pain patients who had found relief with opioids and had discussed this in online forums. While not necessarily a representative sample of all individuals with chronic pain who are on opioids, the survey was informative: 71 percent of respondents said they are no longer prescribed opioid medication by a doctor or are getting a lower dose; 8 out of 10 said their pain and quality of life are worse; and more than 40 percent said they considered suicide as a way to end their pain. The survey was purposely conducted a few months after the CDC released guidelines that many doctors, as well as insurance carriers and state legislatures, have erroneously interpreted as a government mandate to discontinue opioids. In other accounts, patients complain of being interrogated by pharmacists about their doses; sometimes they are even turned away.

The most tragic consequence is suicide. Thomas F. Kline, an internist in Raleigh, North Carolina, has chronicled 23 of them. His count is surely a harbinger of further patient abandonment to come. Meanwhile, so-called pain refugees—chronic pain patients whose doctors have dropped them—search out physicians to treat them, sometimes traveling more than a hundred miles or relocating. And in a recent Medscape survey, half the doctors who were polled expressed fear of violent reactions if patients were refused the prescription.

Knowing all this, what should we do about the opioid crisis? First, we must be realistic about who is getting in trouble with opioid pain medications. Contrary to popular belief, it is rarely the people for whom they are prescribed. Most lives do not come undone, let alone end in overdose, after analgesia for a broken leg or a trip to the dentist. There is a subset of patients who are vulnerable to abusing their medication—those with substance use histories or with mental health problems. Ideally, they should inform physicians of their history, and, in turn, their doctors should elicit such information from them.

Still, given that diverted pills, not prescribed medication taken by patients for pain, are the greater culprit, we cannot rely on doctors or pill control policies alone to be able to fix the opioid crisis. What we need is a demand-side policy. Interventions that seek to reduce the desire to use drugs, be they painkillers or illicit opioids, deserve vastly more political will and federal funding than they have received. Two of the most necessary steps, in my view, are making better use of anti-addiction medications and building a better addiction treatment infrastructure.

Methadone and buprenorphine are opioid medications for treating addiction that can be prescribed by doctors as a way to wean patients off opioids or to maintain them stably. These medications have been shown to reduce deaths from all causes, including overdose. A third medication, naltrexone, blocks opioids’ effect on the brain, and prevents a patient who tries heroin again from experiencing any effects. In 2016, however, only 41.2 percent of the nation’s treatment facilities offered at least one form of medication, and 2.7 percent offered all three medications, according to a recent review of a national directory published by SAMHSA. We must move beyond the outmoded thinking and inertia that keep clinics from offering these medications.

Motivated patients also benefit greatly from cognitive behavioral therapy and from the hard work of recovery—healing family rifts, reintegrating into the workforce, creating healthy social connections, finding new modes of fulfillment. This is why treatment centers that offer an array of services, including medical care, family counseling, and social services, have a better shot at promoting recovery. That treatment infrastructure must be fortified. The Excellence in Mental Health Act of 2014, a Medicaid-funded project, established more robust health centers in eight states. In 2017, House and Senate bills were introduced to expand the project to 11 more. It’s a promising effort that could be a path to public or private insurance-based community services and an opportunity to set much-needed national practice standards.

These two priorities are among the 56 recommendations put forth last October by President Donald Trump’s Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis. Indeed, there is no dearth of ideas. In Congress, more than 90 bills aimed at the opioid crisis have been introduced in the 115th session, dozens of hearings have been held, and later this month, the House Energy and Commerce Committee will begin holding a week of legislative hearings on measures to fight the opioid crisis. The White House’s 2019 budget seeks $13 billion over two years for the opioid epidemic, and the president recently nominated a “drug czar” to helm the Office of Drug Control Policy, though the candidate has minimal experience in the area.

As we sort through and further pursue these policies, we need to make good use of what we know about the role that prescription opioids plays in the larger crisis: that the dominant narrative about pain treatment being a major pathway to addiction is wrong, and that an agenda heavily weighted toward pill control is not enough.

![]()

READING ARGUMENTS

1. In her opening sentence, is Satel appealing to logos, ethos, or pathos? Is this appeal convincing? Why or why not?

2. In the second paragraph, Satel refers to a “false narrative” that has become “conventional wisdom.” What is this false narrative?

3. What is the purpose of paragraph 5? How does it both establish and advance the writer’s argument?

4. In what respects is this a proposal argument? What remedies does Satel recommend? Where in her essay does she make these recommendations?

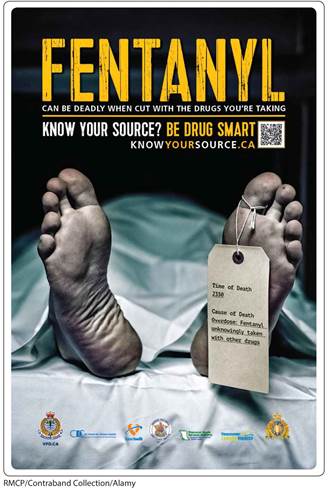

VISUAL ARGUMENT

This public-service poster was created by a Canadian campaign to raise awareness about one particular danger of drug use.

The poster is titled Fentanyl. The subtitle reads Can be deadly when cut with the drugs you’re taking. A line is drawn separating the text below that reads, Know your source? Be Drug Smart. Know Your Source dot C A. A Q R code appears next to the text.

An image below shows a close up of the feet of a dead body covered with a white sheet. A tag is tied to the big toe of the left foot and the text on the tag reads, Time of Death 2330; Cause of Death Overdose; Fentanyl unknowingly taken with other drugs. The text on the tag is underlined except the words Time of Death and Cause of Death.

The logos below the image read, V P D. C A; Centre for Disease Central; Fraser health; British Columbia Ambulance Service; Provincial Health Services Authority; Vancouver Coastal Health; and Maintiens le Droit.

![]()

READING ARGUMENTS

1. Does this visual appeal primarily to logos, pathos, or ethos? Identify an element of each of these appeals in the image.

2. This visual uses both words and images to convey its message and emphasis. In one sentence, summarize this message. Which element (words or images) has the greater impact? Why?

3. This image was part of a campaign from the University of Calgary (Canada) Wellness Center. Who is the intended audience? What specific clues let you know?

![]()

AT ISSUE: HOW SHOULD WE SOLVE THE OPIOID PROBLEM?

1. In “The Myth of What’s Driving the Opioid Crisis,” Satel writes about a “false narrative” that has taken hold with regard to the opioid problem. To what degree are the three other writers in this casebook also addressing “false narratives”? What misleading or mistaken storylines is each trying to correct? Why is finding the “true” narrative so important in solving a problem like this one?

2. Think about how your own knowledge about alcohol, substance abuse, and addiction developed as you learned about them in school, from your friends and parents, from the media, and from medical professionals. What misunderstandings did you have about substance abuse or addiction? Did any of these essays surprise you, or change your mind about anything? Explain.

3. Stanton Peele writes that politicians need to be told that “if they really care about reducing addiction, taking meaningful steps to address inequality and absence of opportunity and to rebuild meaningful community would be the single best thing they could do.” Do you think Ericka Andersen would agree with this statement? How might she respond to it?

![]()

WRITING ARGUMENTS: HOW SHOULD WE SOLVE THE OPIOID PROBLEM?

All the writers here not only address the opioid problem but also provide useful and substantive information about the crisis in their arguments. Write your own essay in which you take a position on this issue. How do you view the opioid problem? What do you see as the best solutions for addressing it?