Practical argument: A text and anthology - Laurie G. Kirszner, Stephen R. Mandell 2019

Casebook: Should the United States have open borders?

Debates, casebooks, and classic arguments

For much of its history, the United States had—for all practical purposes—open borders. Before the United States was established, there was no national government to devise or implement policies on what were, in many ways, fluid and often-contested dividing lines between various nations, colonies, and territories. Moreover, the United States encouraged immigration during the late eighteenth century and much of the nineteenth century. In the era after the Civil War, however, the federal government took a more active role in regulating immigration and border control. The Immigration Act of 1882, for example, required immigrants to pay a fee for entry and blocked certain categories of people from immigrating, including criminals and any individual “unable to take care of him or herself without becoming a public charge.” That same year, the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed, prohibiting the immigration of Chinese laborers. This was the first exclusionary U.S. immigration law based on nationality and ethnicity. During the first part of the twentieth century, waves of immigrants (over twenty-four million, in total) led to more regulation and legislation, including the Emergency Quota Act of 1921. This law placed limits on the number of people granted entry to the United States from any given country.

Throughout the rest of the twentieth century, and now in the twenty-first century, the question of who should be admitted to the United States, and how they should enter the country, has remained problematic, encompassing a variety of complex issues, such as nationalism, crime, sovereignty, national identity, labor, the environment, and the economy. President Donald Trump famously made border security the cornerstone of his campaign, and he has often framed the problem in apocalyptic terms. For example, he once tweeted, “Without Borders, we don’t have a country. With Open Borders, which the Democrats want, we have nothing but crime! Finish the Wall!” In fact, illegal border-crossings have been at historic lows over the past few years. Moreover, illegal immigrants are less likely to commit crimes than native-born Americans. Still, many Americans agree with the president that our borders should be strictly controlled. Not surprisingly, then, border security and immigration continue to be highly polarized issues, even though most people on both sides of the partisan divide agree that new policies are needed. (And few, if any, elected Democrats or Republicans have publicly advocated for a literal “open borders” policy.)

Regardless of their specific viewpoints, all four of the writers whose essays appear in this casebook offer thoughtful, well-reasoned arguments on the topic. In “The Liberal Case for Reducing Immigration,” Richard D. Lamm and Philip Cafaro argue for more restrictive immigration, basing their case on their concerns about preserving jobs for working-class Americans and ensuring environmental sustainability. In “The $100 Trillion Case for Open Borders,” Nick Srnicek makes the case that opening borders (or loosening restrictions on immigration) would be “the single easiest way to improve the living standards of workers around the world—including those in wealthy countries.” John Lee, in “Secure the U.S.-Mexico Border: Open It,” believes that the United States needs a more rational, more discriminating immigration policy that allows the border patrol to focus on bad actors and criminals rather than on “good-faith” immigrants. Finally, Adam Ozimek (“Why I Don’t Support Open Borders”) sees less restrictive approaches as far too risky for the United States, which has too much to lose in the process.

THE LIBERAL CASE FOR REDUCING IMMIGRATION

RICHARD D. LAMM AND PHILIP CAFARO

This piece originally appeared in the Denver Post on February 16, 2018.

As Congress considers potential changes to immigration policy, the debate seems to be breaking down along familiar lines. Conservatives argue for stricter enforcement of immigration laws and reduced immigration numbers, while liberals urge a new amnesty for undocumented immigrants and higher immigration levels.

Yet there are good liberal arguments for combating illegal immigration and reducing historically high legal immigration. Many of these were articulated by the U.S. Commission on Immigration Reform, commonly known as the Jordan Commission, for its chairwoman, liberal icon Barbara Jordan. The Jordan Commission undertook the last comprehensive national study of immigration, publishing its final recommendations in 1997. It would serve the current immigration debate well to take another look at them.

The Jordan Commission began by stating the rationale for making immigration policy in terms of the public good, broadly considered. “We decry hostility and discrimination towards immigrants as antithetical to the traditions and interests of the country,” they wrote. “At the same time, we disagree with those who would label efforts to control immigration as being inherently anti-immigrant. Rather, it is both a right and a responsibility of a democratic society to manage immigration so that it serves the national interest.”

A key aspect of this national interest for the commission was the well-being of working-class people already in the country. Jordan observed that “immigrants with relatively low education and skills may compete for jobs and public services with the most vulnerable of Americans, particularly those who are unemployed or underemployed.” She noted: “The Commission is particularly concerned about the impact of immigration on the most disadvantaged within our already resident society—inner city youth, racial and ethnic minorities, and recent immigrants who have not yet adjusted to life in the U.S.” For these reasons, the Jordan Commission recommended sharp reductions in the numbers of less-educated, less-skilled immigrants coming into the country through chain migration. This, they reasoned, would help maintain employment opportunities for poorer Americans and decrease downward pressure on their wages.

When it came to numbers, the Jordan Commission recommended an overall cut of 40 percent in total immigration. Given the increase in economic inequality since 1997, and forecasts that advances in artificial intelligence, robotics, and other automation technologies could cut millions of blue-collar jobs in coming decades, this recommendation seems more justified than ever—at least for those of us who believe that gross economic inequality is not compatible with a genuinely democratic society.

Like most Coloradans, we also believe in creating an ecologically sustainable society.

“Immigration policies are thus among our most crucial environmental policies—even though we don’t usually think about them that way.”

Climate change, water scarcity in the Western U.S., and other growing environmental challenges make this ever more imperative. While the Jordan Commission said little about the role of mass immigration in driving U.S. population growth, the reality is that current immigration levels are set to double our population to over 650 million by 2100. At reduced immigration levels, our population instead could stabilize at under 400 million over the next three decades. Immigration policies are thus among our most crucial environmental policies—even though we don’t usually think about them that way.

Ending U.S. population growth is the most important step we could take as a nation to create a sustainable society. While that alone won’t create such a society, without it ecological sustainability will be an ever-receding mirage. More people will, inevitably, undermine all the good work we do to use energy, water, and other resources more efficiently. More people will, inevitably, crowd other species off the landscape.

The goal of public policy is to confront new challenges boldly yet realistically. Two great challenges we face in the 21st century are creating an ecologically sustainable society and sharing wealth more fairly among all our citizens. Reducing immigration, and thus reducing economic pressures on less wealthy Americans while stabilizing our population, will go a long way toward helping us meet these challenges successfully.

![]()

READING ARGUMENTS

1. In the second paragraph, the writers refer to the 1997 Jordan Commission, calling its chairwoman, Barbara Jordan, a “liberal icon.” How is their use of this label consistent with their larger argument?

2. Whom do you think the writers see as their primary audience? How can you tell?

3. In its statements about protecting working-class Americans, what causal argument did the Jordan Commission recommendations rest upon? Do you see this as a valid argument? Why or why not?

4. What is the “most important step” Americans could take to create a “sustainable society” (para. 8)? What is the relationship between this “important step” and immigration policy?

5. In what sense is this a definition essay? What is being defined? What specific elements of definition can you identify?

THE $100 TRILLION CASE FOR OPEN BORDERS

NICK SRNICEK

This article appeared on The Conversation on February 8, 2017.

In an ideal world, we would all be able to freely move wherever we wanted. The basic right of people to escape from war, persecution, and poverty would be accepted as a given, and no one would have their life determined by their place of birth.

But we don’t live in this world, and national borders continue to block the freedom of people to move. Around the world, protectionism is on the rise, as people are told to blame outsiders for threatening their way of life and, more importantly, stealing their jobs.

There is, however, an overwhelming case for open borders that can be made even in the traditionally self-interested language of economics. In fact, our best estimates are that opening the world’s borders could increase global GDP by $100 trillion.

That’s $100,000,000,000,000

It sounds like a crazy idea, particularly when the media is dominated by stories about the need to control immigration and the right-wing tabloids trumpet “alternative facts” about how immigration hurts our economies. But every piece of evidence we have says that ending borders would be the single easiest way to improve the living standards of workers around the world—including those in wealthy countries.

The argument is simple enough and has been made by more than one economist. Workers in poorer economies make less than they should. If they were to have all of the benefits of rich countries—advanced education, the latest workplace technologies, and all the necessary infrastructure—these workers would produce and earn as much as their rich country counterparts. What keeps them in poverty is their surroundings. If they were able to pick up and move to more productive areas, they would see their incomes increase many times over.

This means that opening borders is, by a massive amount, the easiest and most effective way to tackle global poverty. Research shows that alternative approaches—for instance, microcredit, higher education standards, and anti-sweatshop activism—all produce lifetime economic gains that would be matched in weeks by open borders. Even small reductions in the barriers posed by borders would bring massive benefits for workers.

Gains for All

Of course, the immediate fear of having open borders is that it will increase competition for jobs and lower wages for those living in rich countries. This misses the fact that globalization means competition already exists between workers worldwide—under conditions that harm their pay and security. UK workers in manufacturing or IT, for instance, are already competing with low-wage workers in India and Vietnam. Workers in rich countries are already losing, as companies eliminate good jobs and move their factories and offices elsewhere.

Under these circumstances, the function of borders is to keep workers trapped in low-wage areas that companies can freely exploit. Every worker—whether from a rich country or a poor country—suffers as a result. Ending borders would mean an end to this type of competition between workers. It would make us all better off.

“Under these circumstances, the function of borders is to keep workers trapped in low-wage areas that companies can freely exploit.”

The European Union has provided a natural experiment in what happens when borders between rich and poor countries are opened up. And the evidence here is unambiguous: the long-run effects of open borders improve the conditions and wages of all workers. However, in the short-run, some groups (particularly unskilled laborers) can be negatively affected.

The fixes for this are exceedingly simple though. A shortening of the work week would reduce the amount of work supplied, spread the work out more equally among everyone, and give more power to workers—not to mention, more free time to everyone. And the strengthening and proper enforcement of labor laws would make it impossible for companies to hyper-exploit migrant workers. The overall impacts of more workers are exceedingly small in the short-run, and exceedingly positive in the long-run.

As it stands, borders leave workers stranded and competing against each other. The way the global economy is set up is based entirely on competition. This makes us think that potential allies are irreconcilable enemies. The real culprits, however, are businesses that pick up and leave at the drop of a hat, that fire long-time workers in favor of cheaper newcomers, and that break labor laws outright, in order to boost their profits.

Borders leave us as strangers rather than allies. Yet this need not be the case, and as a principle guiding political action, the abolition of borders would rank among the greatest of human achievements.

![]()

READING ARGUMENTS

1. What contrast does Srnicek use in his first two paragraphs? Why do you think he chose to begin his discussion in this way?

2. In the second paragraph, Srnicek refers to “protectionism.” What does this term mean? What connotations does it have for him?

3. How would you define the reasoning in paragraph five of this essay? Does it seem to have an inductive or deductive structure? Explain.

4. How would you define the reasoning in paragraph six of this essay? Is it inductive or deductive? Explain.

5. Where do you see elements of a proposal argument in this essay?

SECURE THE U.S.-MEXICO BORDER: OPEN IT

JOHN LEE

This essay appeared on Open Borders, a blog and resource dedicated to making the case for open borders, on February 25, 2013.

The Associated Press has a great story out on what a “secure” U.S.-Mexico border would look like. It covers perspectives from various stakeholders on border security, with opinions running the gamut from “The border is as secure as it can ever be” to “It’s obviously incredibly unsafe.” I am not sure if the AP is fairly representing opinions on the border issue, but the reporting of how life on the border has evolved over time is fascinating.

One thing that strikes me in this reporting is how casually drug smugglers/slave traffickers and good-faith immigrants are easily-conflated. Is a secure border one where people who want to move contraband goods or human slaves illegally cannot easily enter? Or is it one where well-meaning people can be indefinitely kept at bay for an arbitrary accident of birth? This passage juxtaposes the two quite different situations:

And nearly all of more than 70 drug smuggling tunnels found along the border since October 2008 have been discovered in the clay-like soil of San Diego and Tijuana, some complete with hydraulic lifts and rail cars. They’ve produced some of the largest marijuana seizures in U.S. history.

Still, few attempt to cross what was once the nation’s busiest corridor for illegal immigration. As he waited for breakfast at a Tijuana migrant shelter, Jose de Jesus Scott nodded toward a roommate who did. He was caught within seconds and badly injured his legs jumping the fence.

Scott, who crossed the border with relative ease until 2006, said he and a cousin tried a three-day mountain trek to San Diego in January and were caught twice. Scott, 31, was tempted to return to his wife and two young daughters near Guadalajara. But, with deep roots in suburban Los Angeles and cooking jobs that pay up to $1,200 a week, he will likely try the same route a third time.

The main thing that strikes me about the previously “unsecure” border near San Diego is that border patrol agents were overwhelmed by a mass of people until more staff and walls were brought to bear. But these masses of people almost certainly were comprised in large part, if not near-entirely, of good-faith immigrants. Smugglers and traffickers merely take advantage of the confusion to sneak in with the immigrants. If the immigrants had a legal path to entry, if they did not have to cross the border unlawfully, the traffickers would be naked without human crowds to hide in. If border security advocates just want to reduce illegal trafficking, demanding “border security” before loosening immigration controls may well be putting the cart before the horse.

Even so, as I’ve said before, the physical reality of a long border means that human movement across it can never be fully controlled. Demanding totalitarian control as “true border security” is about as unrealistic as, if not even more so than an open borders advocate demanding the abolition of the nation-state.

The AP covers some damning stories of peaceful Americans murdered by drug traffickers in the same breath as it covers someone trying to get to a job in suburban LA. Even if one insists that murdering smugglers and restaurant cooks should be treated identically on account of being born Mexican, it is difficult to see how one can demand that the U.S. border patrol prioritize detaining them both equally. Yet as long as U.S. visa policy makes it near-impossible for most good-faith Mexicans who can find work in the U.S. to do so, the reality of the border means that thousands of Mexicans just looking to work will risk their lives crossing the border, alongside smugglers and murderers.

“The reality of the border means that thousands of Mexicans just looking to work will risk their lives crossing the border, alongside smugglers and murderers.”

The more reasonable policy has to be one that will allow U.S. border patrol to focus on catching the most egregious criminals. That means giving the good-faith immigrants a legal channel to enter the U.S. on a reasonable timeframe, reducing the flow of unlawful border crossings. This is not just my opinion, but that of even a former (Republican) U.S. Ambassador to Mexico:

Tony Garza remembers watching the flow of pedestrian traffic between Brownsville and Matamoros from his father’s filling station just steps from the international bridge. He recalls migrant workers crossing the fairway on the 11th hole of a golf course—northbound in the morning, southbound in the afternoon. And during an annual celebration between the sister cities, no one was asked for their papers at the bridge. People were just expected to go home.

Garza, a Republican who served as the U.S. ambassador to Mexico from 2002 to 2009, said it’s easy to become nostalgic for those times, but he reminds himself that he grew up in a border town of fewer than 50,000 people that has grown into a city of more than 200,000.

The border here is more secure for the massive investment in recent years but feels less safe because the crime has changed, he said. Some of that has to do with transnational criminal organizations in Mexico and some of it is just the crime of a larger city.

Reform, he said, “would allow you to focus your resources on those activities that truly make the border less safe today.”

It’s the view of those sheriffs who places themselves in harm’s way to fight those murderers and smugglers:

Hidalgo County Sheriff Lupe Trevino points out that drug, gun, and human smuggling is nothing new to the border. The difference is the attention that the drug-related violence in Mexico has drawn to the region in recent years.

He insists his county, which includes McAllen, is safe. The crime rate is falling, and illegal immigrants account for small numbers in his jail. But asked if the border is “secure,” Trevino doesn’t hesitate. “Absolutely not.”

“When you’re busting human trafficking stash houses with 60 to 100 people that are stashed in a two, three-bedroom home for weeks at a time, how can you say you’ve secured the border?” he said.

Trevino’s view, however, is that those people might not be there if they had a legal path to work in the U.S.

“Immigration reform is the first thing we have to accomplish before we can say that we have secured the border,” he said.

In Nogales, Sheriff Tony Estrada has a unique perspective on both border security and more comprehensive immigration reform. Born in Nogales, Mexico, Estrada grew up in Nogales, Ariz., after migrating to the U.S. with his parents. He has served as a lawman in the community since 1966.

He blames border security issues not only on the cartels but on the American demand for drugs. Until that wanes, he said, nothing will change. And securing the border, he added, must be a constant, ever-changing effort that blends security and political support—because the effort will never end.

“The drugs are going to keep coming. The people are going to keep coming. The only thing you can do is contain it as much as possible.

“I say the border is as safe and secure as it can be, but I think people are asking for us to seal the border, and that’s unrealistic,” he said.

Asked why, he said simply: “That’s the nature of the border.”

Simply put, if you want a secure U.S.-Mexico border, one where law enforcement can focus on rooting out murderers and smugglers, you need open borders. You need a visa regime that lets those looking to feed their families and looking for a better life to enter legally, with a minimum of muss and fuss. When only those who cross the border unlawfully are those who have no good business being in the U.S., then you can have a secure border.

![]()

READING ARGUMENTS

1. Lee begins by discussing an article on border security from the Associated Press. Why does he find the AP’s coverage “fascinating”?

2. In paragraph 6, Lee identifies a “more reasonable policy” toward immigration. What is this policy? Why does he support it?

3. Where does Lee appeal to ethos? Point to a specific example and explain how the appeal works.

4. In Lee’s view, what is the connection between immigration reform and a secure border policy? Do you see this connection as key to solving our immigration crisis, or do you think Lee is exaggerating its importance? Explain.

WHY I DON’T SUPPORT OPEN BORDERS

ADAM OZIMEK

This piece was published by Forbes on February 26, 2017.

I am a big fan of immigration, and I think we can easily absorb significantly more immigrants than we do right now. But I am not a proponent of open borders, and I thought it would be useful to give a few fairly high level reasons why.

The big, fundamental meta question to me is: why is the U.S. richer than the countries that most immigrants are coming from? It’s a combination of different levels of physical capital, human capital, technology, social capital, and institutions. But the last two are extremely vague, and our knowledge of how institutions and social capital emerge and evolve is not great. A decent amount of immigration only changes these things slowly, but open borders could change them very quickly.

Would these changes be positive or negative? We don’t know, but given that the U.S. is already very rich compared to the rest of the world the risks are to the downside.

That said, if we could do better at directing immigration to parts of the U.S. I think in some places the risks of massively increasing immigration flows are outweighed by the benefits. Detroit, for example, is not doing nearly as well as the U.S. overall. Ranked as a country by itself, one would not describe it as doing so well that the risks are mostly to the downside.

It’s true the U.S. overall has undergone successful massive changes in the past, including due to large influxes of immigrants. According to a recent National Academies report, the largest period of immigration influx as a share of population since 1790 was from 1850 to 1860 when net international migration was 9.8 per 1,000 U.S. population. That’s about triple today’s rates, and would translate to about 3 million immigrants a year. I’m fine with that rate, it seems like a pretty aggressive expansion, and I’m not sure why we’d want to start with something a lot higher than that. I think the risks outweigh the rewards for pushing significantly above that.

The case against massive changes in the U.S. is also stronger today than it was in the past. It was easier to support massive radical changes in previous centuries when we were constantly in the midst of huge fundamental changes like the end of slavery, the rise of democracy, the industrial revolution, World Wars, and the emergence of the welfare state. In general, when we questioned the status quo in the past we can say that the status quo was a result of recent massive changes. In the past we also hadn’t gone very far in terms of well-being compared to previous centuries. But now, on the other side of two industrial revolutions and 100 years of productivity growth, we have far much more to lose.

We’re in an era of far fewer massive changes, and the U.S. is a big country that is near the top of the list development-wise. If we’re going to step outside of modern experience, I’d rather see it done somewhere else first.

“But now, on the other side of two industrial revolutions and 100 years of productivity growth, we have far much more to lose.”

Some, like the excellent Alex Nowrasteh, say we should wall off the welfare state from immigrants and natives rather than wall off the country. I think the welfare state is an important source of upward mobility and a driver of life-time well-being for natives and immigrants. I take his proposal as actually kind of telling about the sort of radicalism that might be required to potentially sustain open borders. Rather than spend a lot of energy arguing on behalf of things like public schools, food stamps, Medicaid, and the Earned Income Tax Credit, I’d rather simply point to this proposal and say “See? This kind of bad solution is what could potentially be required to sustain open borders!”

So that’s my big vague case against open borders! We don’t really know enough about what generates the wealth of nations to make massive changes like this. It is very plausible that the people in a country play a big role in determining the wealth of that country, and the downside risks of massive changes in the U.S. tend to outweigh the upside risks.

![]()

READING ARGUMENTS

1. Why do you think Ozimek opens his essay by claiming to be a “big fan of immigration”? What does he gain by making this assertion?

2. In his second paragraph, Ozimek writes, “The big, fundamental meta question to me is: why is the U.S. richer than the countries that most immigrants are coming from?” What does he mean by “meta question”? Why is he asking this question?

3. Ozimek refers to “social capital” but claims that the term is “extremely vague” (para. 2). How would you define this term?

4. According to Ozimek, the “case against massive changes in the U.S. is also stronger today than it was in the past” (6). How does he explain this statement?

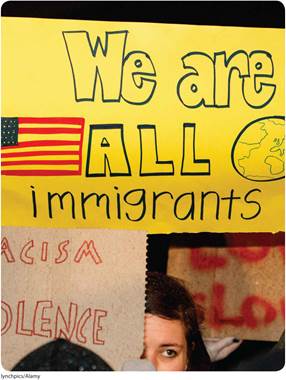

VISUAL ARGUMENT

This image of families at the U.S.-Mexico border appeared in an ABC news story.

![]()

READING ARGUMENTS

1. This image is from an ABC News story about a Facebook campaign to raise money for immigrant families who have been separated at the U.S. border. What message does this image convey? What is your reaction to this message?

2. Describe the people who appear in this photograph. How does their presence affect your response to the image?

3. Which elements of this image are shown in sharp focus? Which are blurred? Do you think this difference in focus was intentional? If so, why did the photographer make this choice?

![]()

AT ISSUE: SHOULD THE UNITED STATES HAVE OPEN BORDERS?

1. Both Srnicek and Ozimek ground their arguments in the context of immigration and economic prosperity, but they reach different conclusions and support different approaches. Which writer do you find more persuasive, and why?

2. How do you think Lamm and Cafaro would respond to Srnicek’s argument? Do you think they would agree on certain issues? Which ones?

3. The writers in this casebook address the question of borders and immigration in the context of different issues and problems, from crime and the environment to the job prospects of the American working class. After reading these four essays, what do you think is the most pressing issue related to border security and immigration?

![]()

WRITING ARGUMENTS: SHOULD THE UNITED STATES HAVE OPEN BORDERS?

After exploring this issue from a variety of angles, what is your view of the problem? Write an argument essay that takes a position on whether or not the United States should have open borders. (Alternatively, you may argue either for more restrictive immigration or less restrictive immigration—or for some other policy change outside the binary choice between open borders and no open borders.)